January Saint

By Fr Mervyn Duffy SM

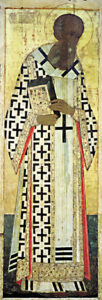

St Gregory Nazianzen

Andrei Rublev, Gregory the Theologian(1408)

2 January

I teach seminarians and theology students about the importance of the Ecumenical Councils and Gregory was one of the major players in the Council that produced the second part of the Creed we say at Mass. He is the great champion of the Holy Spirit as a person of the Trinity rather than merely a force. In the Eastern Church he is one of only three saints with the title ‘the Theologian’.

Gregory was born near Nazianzus in Cappadocia (southern Turkey). His father was appointed Bishop of Nazianzus shortly after Gregory was born. They were a wealthy Greek family. Originally home-schooled by his uncle, Gregory showed such academic promise that he was sent to study rhetoric at Nazianzus, Caesarea, Alexandria and then Athens. During his time as a student, he met a future emperor whom he was to oppose, Julian the Apostate, and made friends with Basil who was to be Bishop of Caesarea and a life-long collaborator.

In 361, at his father’s insistence, he returned to Nazianzus and was ordained as a priest. He had hoped for life as a monk and poet. A dozen years later his friend Basil wanted support in synods where he was dealing with Arian bishops. He, and Gregory’s father, decided the best thing to do would be to install Gregory as the bishop of Sasima – a very small town that would not have otherwise qualified to have a bishop. Gregory went along with the plan, being ordained bishop in 372, but he described Sasima as an “utterly dreadful, pokey little hole; a paltry horse-stop on the main road... devoid of water, vegetation, or the company of gentlemen” and he did not spend much of his time there, preferring to be in Nazianzus acting as coadjutor bishop to his father who was very unwell.

In 374 both Gregory’s parents died. Gregory acted as administrator of the diocese of Nazianzus but refused to be named as bishop of the city. He gave away most of his inheritance to the poor, lived a very ascetic lifestyle, and, at a monastery nearby, managed to live for three years, as the monk he wanted to be. .

Gregory had established a reputation through his theological writings and when the preparations began for an ecumenical council to continue the work of the Council of Nicaea he was asked by the Archbishop of Antioch to lead their delegation. There were then three major centres of ecclesiastical power: Antioch, Alexandria and Rome. They all wanted to ensure the unity of the Christian faith in the empire and that the capital city, Constantinople, had a bishop they could rely on. In the run up to the Council, while in Constantinople, Gregory preached a series of wonderful sermons on the Holy Spirit which gained him considerable popular acclaim.

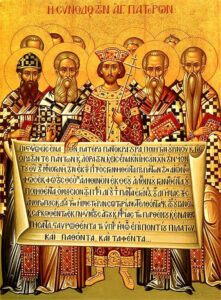

Icon depicting Constantine I, accompanied by the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325), holding the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381

The First Ecumenical Council in 325 had produced a creed mainly about the divinity of the Son of God, using phrases like “light from light” “true God from true God”, “begotten not made”, but when it came to the Holy Spirit all it had said was “we believe in the Holy Spirit”. The theological issue of the day was whether God was a Trinity of three persons, whether the Holy Spirit was a divine person like God the Father and God the Son. There were Bishops who were happy to baptise in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, but fought against the idea of the Spirit as a divine person. They were known as ‘the Pneumatomachi’ – the fighters against the Holy Spirit.

In the spring of 381, bishops started gathering in Constantinople for the Ecumenical Council. Thirty-six of the Pneumatomachi group refused to sign the Nicene Creed and were not admitted. The legates of the Pope and the many bishops from Alexandria were yet to arrive, but the Antioch party decided to get the Council started. About 150 bishops, with Bishop Meletius of Antioch presiding, began the Council and promptly deposed the Bishop of Constantinople, Maximus, who had been consecrated in a clandestine fashion. They then declared that Gregory was the Bishop of Constantinople. It would be hard to find a diocese more different from Sasima.

Quite suddenly, Bishop Meletius, the president of the Council, died. The Council members elected Gregory, Bishop of Constantinople, as president to continue the Council.

Next the Alexandrian bishops arrived from Egypt. They had backed Maximus as Bishop of Constantinople and were not happy that Gregory was now both bishop of that city and president of the Council. They pointed out that the Council of Nicaea had a canon (widely ignored) against the transferring of bishops from one diocese to another.

Finally the legates from the Pope arrived from Rome. They were against Maximus, but also against transferring bishops.

Gregory wanted the Council to bring about unity in the Church on the issue of the Holy Spirit and the Trinity, but the Council was falling apart and engaging in in-fighting about him. He figured that the way to get the Council on task was for him to get out of their way. With the consent of the Emperor, and to the complete shock of the Council, he resigned as Bishop of Constantinople and stepped down as president of the Council. Gregory went back to Nazianzus as the Council continued but his influence is evident in how they extended the Creed:

And in the Spirit, the holy, the lordly and life-giving one, proceeding forth from the Father, co-worshipped and co-glorified with Father and Son, the one who spoke through the prophets; in one, holy, catholic and apostolic church.

We confess one baptism for the forgiving of sins.

We look forward to a resurrection of the dead and life in the age to come. Amen.

After two years of caring for the people of Nazianzus, Gregory retired nearby to his birthplace, Arianzo, where he studied, prayed, wrote poetry and his autobiography.

He died about the year 390.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)