The Way of St James: France

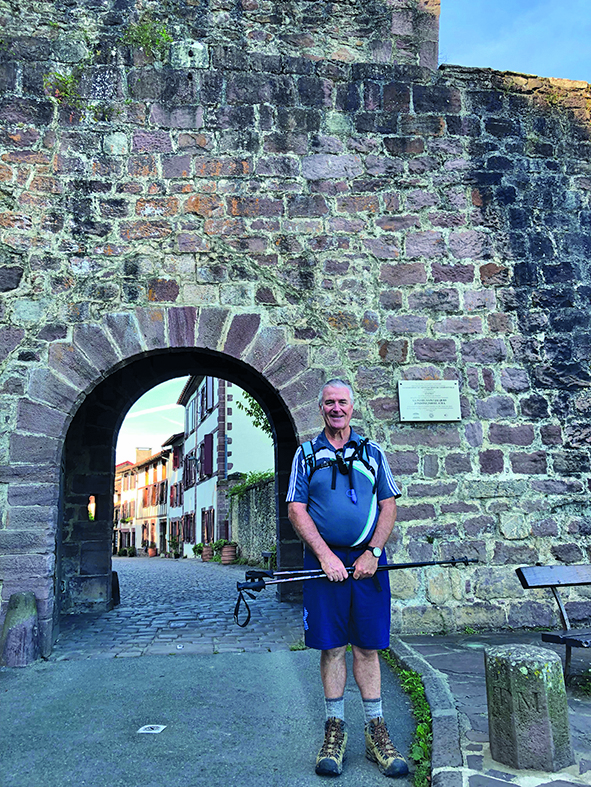

Le Puy-en-Velay to the Pyrénées, 2 September - 8 October 2019

On the afternoon of the second day of this journey, I was sitting with the owner of a little pub in Monistrol d’Allier where I was staying, watching him peel enormous mushrooms that were the local delicacy, but which looked to me more like the stuff in New Zealand forests we were taught as kids to avoid.

Peter is an Englishman, a former teacher, who came here twenty years ago. He lives and loves the Camino, and knows every inch of it. He literally serves the pilgrims, making their rooms ready, cooking their meals, drying out their wet clothes, binding up blisters. However, even though they are his bread and butter, he has little time for the ‘holiday-makers’. He thinks eighty per cent of those who come through his pub in the ‘season’ are now holiday-makers. “They walk a week each year, they make a lot of noise, but they miss the point. They don’t ever go long enough, or hard enough, to self-reflect. You have to be on the trail long enough, and sweat your way up the steepest hills day after day, to realise that other people in your life aren’t the nasty ones. You’re the nasty one ... and once you realise that, you can tune into the Almighty because the Almighty can tune into you. Write to me, will you, and tell me how long it takes for you to get to that point”.

Peter’s homespun wisdom probably wouldn’t make it into any camino guide-books, but he does capture some of the essence of the pilgrimage. It is physically challenging. The hills, especially in the first half of this French section, are very steep and often quite relentless, some descents are like almost vertical river beds, and the weather conditions mean constant adaptation. The self-reflection comes because you know you are testing yourself, and you have to wonder, constantly, if you will be up to the test. There’s over a month of this ahead of you, there’s silence and solitude, and even with other people on the trail, the usual distractions of life just aren’t there anymore, and ultimately the inevitable happens. Peter reckoned it would take about ten days. It didn’t.

You can think of yourself as just another pilgrim, or you can be awed by the fact that millions of others have passed this way since the first pilgrims did so sometime in the ninth century. You can wander the cobbled streets of Figeac and St-Côme-d’Olt and Estaing and remember that villagers have been smoothing these stones since the Middle Ages. You can sit in the cathedral at Conques, a mediaeval village that clings precariously to the side of a hill above the river Lot, and listen to the Norbertine monks chanting the Prayer of the Church as they sit in choir. Even the tourists from the buses are hushed by the sounds of this ancient liturgy. You can walk along the Cami Ferat, the Iron Road, built by the Romans between Limogne-en-Quercy and Lalbenque over two thousand years ago. You can sit in the scores of tiny chapels along the pilgrim route that commemorate this local saint and that, and reflect that people like you have done this for the last eleven hundred years. You can be just another pilgrim, or you can become a part of this history.

The trail at Golinhac, part of the original 9th century Way of St James

A Pilgrim Cross, more than twelve hundred years old

We often tell the students on our programmes that God speaks to us through the people and events of our lives. From the early days of this pilgimage I felt that God was shouting. I could hear, loud and clear. The challenge, now, was to listen.

Apart from the very personal aspect of walking the Camino, there is so much of human interest as well. The French countryside is beautiful. As I expected, it changed over the period of five weeks as I came closer to the Pyrénées. The steep hills and deep gullies of the Lot Valley gave way to rolling countryside, corn fields, vineyards and small cattle holdings. Villages and hamlets are often close to each other but fiercely independent. Most have their own church, often magnificent structures that once served much bigger populations. Every town has its war memorial, often recording the death of five and six members of the same family. Castelnau-sur-l’Auvignon, a tiny, single-street village, has its own proud history as a home of the French Resistance. Display boards along the roadside tell the story, especially of Jeanne Robert, the nineteen-year old school teacher who was the local organiser. As I stood reading her extraordinary story, an old local man materialised beside me, his finger stabbing at her picture: “She was my teacher over there in the school”. The school is named in her honour.

Medieval bridge, Cahors

Stone-carved tympanum

on the Cathedral in Conques

Everywhere, throughout the countryside and in the villages, overt signs of a past, vibrant faith abound. There are the ubiquitous wayside crosses, the churches and chapels, but especially statues of the Virgin Mary. The history of many in the countryside does not seem to be part of the public record, but many statues in the villages recall parish missions, or forty-hour devotions, of some past years and a different era of religious observance. The churches are well looked after and often have fresh-cut flowers at the altar, but most now see Mass only infrequently. Inside the porch of the huge church in Navarrenx there is a graphic showing the twenty-five churches that make up the parish of Navarrenx. All are within a twenty-kilometre radius. There is at least one Mass in each of them sometime in every two months. The majority of priests serving in these relatively remote places are French-speaking Africans.

The ancient trail of the Camino Frances provided a wonderful context for an extended period of prayer and reflection. Setting out from Le Puy-en-Velay, with its Marist connection, was something of added significance for me. Having even limited French was a help, and I found my French hosts in each village so friendly and accommodating. One host even told me over the phone the code to the front door of the hostel, how to find the register to check my room number, and where to find the key. He was out picking mushrooms for dinner. And, of course, food is an art form for the French. The local speciality was always on the menu, and I ate many things I might not have otherwise chosen. But over all it was the silence, the solitude, the sense of history, the time to reflect, to pray, to remember, to anticipate, that made this experience what it was, the journey rather than the destination.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)