Who are you, Jesus?

Fr Tom Ryan sm

1. ‘Our wisest and dearest friend’

‘Who are you Jesus?’ The question triggers as many answers as there are people.

The four Gospels, for instance, present four portraits of Jesus from early Church communities. Jesus is seen from different angles: the suffering Son of Man (Mark); the New Moses (Matthew); the universal and compassionate Saviour (Luke); Son of God and Word made flesh (John).

Closer to our time, Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky was absolutely captivated by the Gospel Jesus. In a paradoxical comment, he said that if someone could prove Christ was outside the truth, he would choose Christ.

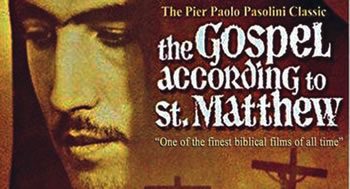

In the 1960s, film director Pier Paoslo Pasolini found himself in a hotel room with nothing to read. He picked up the Bible. He did not put it down till morning. He, too, was fascinated by Jesus in the Gospels and, hence, his film, The Gospel According to Matthew.

In the 1960s, film director Pier Paoslo Pasolini found himself in a hotel room with nothing to read. He picked up the Bible. He did not put it down till morning. He, too, was fascinated by Jesus in the Gospels and, hence, his film, The Gospel According to Matthew.

Australian poet Vincent Buckley was struck by the personal magnetism of Jesus. He overwhelms all our expectations. For Cardinal Avery Dulles it was the unexpected in Jesus: could we humans ever design a God like the one revealed in Jesus (one of spendthrift love)?

Another answer is found in a beautiful phrase from Thomas Aquinas. When he discusses the New Law (the Holy Spirit dwelling in us), Aquinas says that Jesus, in guiding us by his counsel, is our wisest and dearest friend. In this article, we consider Jesus as ‘our dearest friend.’

Our dearest friend

What does it mean to be friends with God? Another word to describe it is ‘charity.’ This is the love with which Christian living begins, grows and is completed. In friendship, we give ourselves away and yet come to be what God ‘in perfect love, has always wanted us to be’ (Wadell, pp. 120-1).

Thomas Aquinas suggests that friendship is not just a state, a relationship. It is a virtue. It is an enduring disposition to discern, respond to, and choose to do, what is truly good, with increasing ease and pleasure. It is to love God, and others, in a certain way. How, exactly?

First, one desires and strives to achieve the friend’s best interests, well-being and happiness. We evaluate things in terms of what is best for the friend’s sake, or for what will nourish the relationship. With God, we want what God wants, make God’s well-being our own. In so doing, we cooperate with God in achieving our own well-being and happiness, since that is precisely what God wants for us.

Detail from The Triumph of St Thomas Aquinas, between Plato and Aristotle,

Benozzo Gozzoli, 1471. Louvre, Paris

Second, the friendship is mutual. Friendship entails a love in which the desire to promote the other’s well-being is returned by the other person. It means a willingness to share a friend’s pain. With God, it resembles a type of equal standing between friends, as if we and God can look each other in the eye. It also means that friends who never spend time with each other do not stay friends for long, which says something about our prayer.

Finally, the bond of love between friends means that each becomes for the other another self. We are also transformed by our friends. It is their love that forms us into what we hope to become (Wadell, p. 135).

Self-Giving Friendship

When we think of these qualities and our relationship with Jesus, there is, however, something a little different. Jesus says, "I shall not call you servants anymore because a servant does not know his master’s business" (John 15:15). Why? Jesus reveals to us what he knows of his Father. For that reason, He says "I call you friends." It is precisely as friends of Jesus that we are called to be servants, in imitation of Jesus.

This is captured in two quotes. Jesus says that a person can have no greater love than to lay down his life for his friends (John 15: 13).

In Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, Sidney Carton, replacing his friend and awaiting execution, says, It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest, that I go to, than I have ever known (III, 15).

In Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, Sidney Carton, replacing his friend and awaiting execution, says, It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest, that I go to, than I have ever known (III, 15).

Ryan Salvatore Giuliano

Finally, friendship involves risk. I remember, as a young boy, reading in the paper about a young man called Salvatore Giuliano who led a short-lived rebellion in Sicily against the civil and military authorities in the 1940s and 50s. He was lured into a town square and shot.

Before his death, he foresaw his fate with realism and insight, tinged with sadness. The words have haunted me since: I can look after my enemies but God protect me from my friends.

Could these also have been the words of Jesus?

Perhaps we could ponder that question and read Chapter 15 of John’s Gospel.

Source: Paul Wadell, Friendship and the Moral Life (University of Notre Dame Press, 1989).

Fr Tom Ryan sm is a Marist priest who lives in Sydney.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)