An Introduction to the Stories of Luke

About 30 CE on the feast of Shavuot, the annual Jewish festival celebrating the disclosure of God’s Law to Moses on Mt Sinai, Peter became the first person to address a Jewish crowd to tell them the good news of Jesus the Christ. This feast is celebrated fifty days after Passover and often referred to as Pentecost, the Greek word for fifty days. Pentecost was the name Christians adopted to commemorate the coming of the Holy Spirit that very day.

Peter’s message was succinct: the good news of Jesus is for everybody. Just over a month earlier Peter had been unable to face a small group of bystanders when he denied that he even knew Jesus and now, inspired by the Spirit, was giving details of his life-changing experience. The gift he had received was being made available to anyone who cared to learn about it and accept it.

As Peter told them, God had done amazing things for himself and the original band of disciples as well as working through them. God was also prepared to give the very same gifts to everyone in the very large crowd that had gathered, probably because of the commotion caused by the advent of the Holy Spirit. But wait, there is more! The invitation was extended to the families of those listening. Peter was so persuasive that over three thousand people accepted the invitation. Is it any coincidence that this number equalled the total people killed by the sons of Levi as a result of the idolatrous worship of the golden calf (Ex 32:28)?

The enthusiasm of the original disciples, aided in no

small measure by the Spirit, was infectious and the movement was to spread quickly across the Roman world before crossing into distant and unknown territories. This spread of the good news, while all well and good, needed to circumvent the ill-discipline of a game of Chinese Whispers. The fledgling church wanted to find ways of preserving the Master’s message, particularly once it became apparent that the Second Coming was no longer imminent. Further, it became necessary for contact to be maintained with local churches in order to safeguard accepted beliefs. Accordingly church leaders issued letters to those they had evangelised, encouraging their members and perhaps correcting misinterpretations that had developed. These were to become known as the Epistles and form much of the New Testament.

In these early days of the church, many stories concerning Jesus had been disseminated widely by word of mouth. Eventually some followers became inspired to record them for posterity and facilitating a more extensive hearing of the narratives. Thus the Gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke and John came to be written which, together with Acts and the Book of the Revelation to John, now comprise the New Testament.

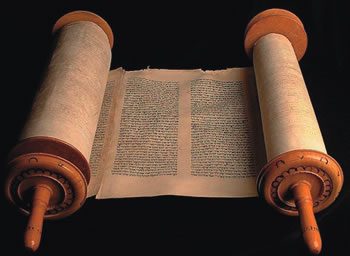

The work of the man we have come to know as Luke was rather more extensive than that of the other evangelists for he had collected sufficient information to complete two papyrus scrolls, the normal medium of his day for writing. Scrolls were usually some thirty two feet long and this very clever writer designed his masterpiece to address separate periods in his two scrolls. The first narration was about the time of Jesus’ physical presence on earth (up until the Ascension) and became known as a gospel. Luke did not name his second volume, which provided a history of the foundation of the church; it would not be until late in the 2nd century that it was entitled the Acts of the Apostles.

The work’s history suggests that the two scrolls were intended to be read as a single narrative: nonetheless their separation was to be finally settled once the use of scrolls was discontinued after the implementation of the codex, an early book format. The relationship between Luke’s Gospel and Acts has prompted Bishop Tom Wright to assert: We call it ‘The Acts of the Apostles’, but in truth we should really think of it as ‘The Acts of Jesus (II)’.1 Paul Walaskay agrees with the bishop’s proposition but chose a different name: He might have entitled his two volumes “The Acts of God.”2

No-one can know what Luke was intending when he wrote his two manuscripts but obviously he would have had something in mind. Educated guesses suggest several hypotheses but not everyone will agree with them all. Paul Walaskay has recognised three basic groupings which might cover his intentions: Education, Theology and Apologetics.

The dedication of his Gospel makes it quite clear that Luke was looking to educate and enlighten members and supporters of the church through his writings: I too decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first, to write an orderly account for you, … (Lk 1:3)3. The quality of Luke’s writing indicates that it was produced for the benefit of literate and well-connected members of the society in which he worked: he was able to demonstrate that Christianity deserved to be heard among other religious and/or philosophical teachings.

Christianity is not simply a provincial sect of Judean Judaism. Rather, it is a world-embracing religion equal to the best thinking and believing of the day.4

Further, his work seems to have been so easy to understand that those who read his work would have been able to use it as a tool for the instruction of catechumens.

Throughout his two volumes Luke, in developing his theology, was concerned to demonstrate the ways in which God worked through Jesus, his apostles and disciples. His narrative commenced with Mary’s pregnancy, continued through the years of Jesus’ birth, mission, passion and death, resurrection and ascension, dealt with the establishment of the church and ended with Paul’s time in Rome. Paul’s last two years were spent proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance. (Acts 28:31). The story of Jesus’ life and death naturally concentrated on God working through Jesus. Acts then describes the absolute wonder of the way in which God carries on working through humanity, revealing his grace and forgiveness and making it available to all. In Acts the God of the Jews becomes the God of the Gentiles and moves to wipe out all distinctions between the sexes, between nations and between rich and poor.

Apologetics is that branch of theology which seeks to proclaim the truth of Christianity and to encourage adherents to live the faith within their own society. God’s desire for total equality has been rejected in both major and minor ways, so was Luke looking to provide a defence aimed at shifting political attitudes towards Christianity and seeking to improve its members’ legal standing? If so he succeeded to a limited degree. Persecution was to become a fact of life for many at various times, under different authorities and in separate parts of the empire. Christians also needed to come to terms with living in a society with which they were at odds, often over questions of faith.

Some features of Roman society did not interfere with Christian beliefs. The pax romana, the “Peace of Rome,” facilitated travel, allowing the disciples to journey widely around the Mediterranean and even further afield, visiting their burgeoning local churches. Clearly Luke was anxious to show that the Old Testament prefigured the Christ and, as a result, the church itself: hence, Gentile converts needed to be taught that the covenantal traditions of Judaism were foundational to Christianity. Doesn’t this need to be rediscovered by Catholics today? Of course, Judaism itself had special privileges under Roman law and if the church were recognised as a Jewish sect it would be able to coat-tail on those privileges.

One other objective may have been that Luke wished to soften the message of Paul which sometimes was perceived to be quite anti-law to the point that his total message was being disregarded. Luke’s portrayal of Paul shows him being compliant with the leaders in Jerusalem; although that may be a representation showing Paul to be more accommodating than he really was.

Whatever Luke’s intent he certainly achieved the orderly account his introduction embarked on once he put pen to papyrus. 5

Footnotes

1 Tom Wright, Acts for Everyone, Part 1: Chapters 1-12 (London: Society for Promting Christian Knowledge, 2008), 2.

2 Paul W. Walaskay, Acts, ed. Patrick D Miller and David L Bartlett, Westminster Bible Companion (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998). 13.

3 Paul W. Walasky, 12.

4 Paul W. Walasky, 13.

5 Paul W. Walasky, 14.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)