Christ our Light and Companion

Easter Vigil

See Readings Saturday 4th April - page 19

In the Eucharist’s Offertory prayer, we bless the ‘God of all creation’. From his ‘goodness we have received’ gifts: of bread - ‘work of human hands’ and of wine - ‘fruit of the earth’, to be transformed into our spiritual food and drink.

This is a prayer of gratitude for our material world, one that could embrace the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s four elements of matter: earth, air, fire and water. These are not just the basic ingredients of our planet, even of creation itself. Each is, in some way, essential to life.

Tonight’s liturgy begins by returning to those basic elements in God’s gift of our world. We use, especially, fire and water, to express the realities of our faith and of God’s loving dealings with us, past and present. Through these ‘gifts’ and the ‘fruits of the earth’ God’s presence and action continues in our midst. We describe this as the sacramental nature of reality: the invisible reaches us through the visible. As our guide in these reflections, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ, said:

“By means of all created things, without exception, the divine assails us, penetrates us, and molds us. We imagined it as distant and inaccessible, when in fact we live steeped in its burning layers.”

Tonight, Christ is present when the Word is proclaimed, in the various rituals, prayers and gestures, in the sacraments of Baptism and, most importantly, in the Eucharist – the summit and source of the Church’s life.

Let’s consider one element central in tonight’s liturgy, namely, fire.

What did it feel like when our human ancestors, long ago, first discovered fire? No doubt, they would have experienced its presence from nature’s activities. But to create fire is quite different. Now, they could harness its energy, in heat for food, in protection against the extreme cold, in light amidst darkness, as a focal point for comfort and companionship.

In many ways, these are the primordial, ‘human family’ memories tapped in the Easter vigil. But they also reflect our need to nourish the whole person, given our spirit/body makeup. Through the use of our embodied experience and material resources, we also express our deeper hungers, our desire to find meaning and love. Again, de Chardin notes:

“By virtue of Creation, and still more the Incarnation, nothing here below is profane for those who know how to see.”

In our Christian story, Christ is our light. He accompanies us in that search, especially in times of difficulty and pain. He has overcome darkness’ – forces of evil and sin that oppose the God’s love and goodness and the destiny of creation. In the ‘Exultet’, we celebrate what Jesus has done and does in his Church and in our world. We remember his victory - his rising to new life. We renew our faith and commitment to him in the Baptismal promises. We share in his gift of himself to the Father and receive his gift of himself to us in his body and blood.

I conclude with two points: first, a final quote of de Chardin:

“Some day, after we have mastered the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love. Then for the second time in the history of the world, we will have discovered fire.”

Second, in her writings, Thérèse of Lisieux, at times, refers to the Trinity in terms of the ‘fire’ or ‘furnace’ of divine love. She uses this language when she wants to convey her longing to be with God, the desire for heaven. The English translation does not quite capture the original word in French. Thérèse uses the word ‘foyer.’ This can mean, as in English, an entrance area, a vestibule in a house or office. In French, it is also used to denote the domestic hearth.

For Thérèse, ‘foyer’ evoked a glowing domestic hearth or fireplace with all the family gathered around it. Imagine the scene: a cold winter evening, people making toast over the open fire, sipping hot soup, savouring the mulled wine - the play of light and shade from the flames on the surrounding faces. Think of the rich associations: warmth, security, peace, nourishment, joy and, most important of all, the sense of belonging.

Visitors arrive. There is a warm welcome. They are given soup and toast. There is shuffling to make room for the guests.

This is the God of the Trinity’s family – where there is always space for another, and another, and another…. and, in fact, for all of creation.

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one

TS Eliot: Little Gidding.

Easter Sunday

Christ our Light and Companion

See Readings Sunday April 5th - Page 20

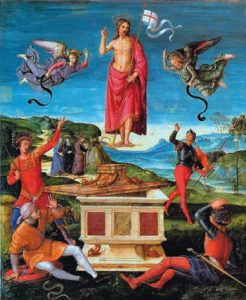

Easter Sunday’s significance is perhaps best captured in Paul’s words from the Easter Vigil: “As Christ was raised from the dead by the Father’s glory, we too might live a new life.”

It is interesting to sense the mood of the Church’s liturgy on Easter Sunday and the days that follow. It is less one of exuberance and triumph more one of wonder and subdued joy. Being too much for words – awe-filled Easter as with the awful Good Friday – time is needed to absorb what has happened. This is true for the witnesses, the disciples, the community in Jerusalem and all those who live by faith. Faith can only gradually understand and appreciate (and never fully in any way) what we now call the ‘Paschal Mystery’- the new creation brought into existence by Jesus’s suffering, death and resurrection.

Look at the journey of one disciple. We remember a fearful Peter, huddled around a fire, denying any association with Jesus the night before his death (Mark 14). In today’s Gospel passage from John, we see him with another disciple move from lack of faith to the beginnings of resurrection faith. The reader knows that the Beloved Disciple is ‘the one Jesus loved’ in a special way, while Peter, despite his fragility, is the ‘Rock’, namely, a bearer of authority and a spokesperson. It has been suggested that John’s gesture of courtesy in waiting for Peter to be the first to enter the empty tomb is recognition of Peter as ascribed leader. Finally, in the first reading from Acts, we see Peter as a fearless leader proclaiming the crucified and risen Lord and his message.

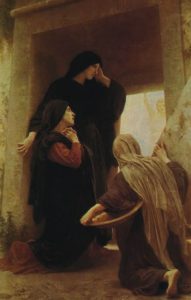

Or think about the effects on the communities of the early Church, as reflected in the four Gospels. In the accounts of the resurrection events, the women are central. They do not so much witness but rather witness to the resurrection. What they experience are ‘the signs or traces of the divine activity that has brought it about’ (Brendan Byrne, Lifting the Burden, 222).

Overall, the women emerge with more credibility than do the men when it comes to openness to faith and the workings of God. Again, there is no effort to ‘doctor’ the traditions in which the first witnesses to the Resurrection are women, whose testimony, in the culture of the time, had no legal standing. The presence of such unusual and unexpected incidents in the Gospels is an indicator of their authentic quality.

Let’s return to the sense of understated conviction and calm noted above. It can remind us of what we can expect of liturgy.

Don Saliers describes liturgy as the divine ethos of God’s self-giving to us ‘where grace and glory find human form’ and which draws into itself human pathos (human emotions, suffering and sinfulness). He explains beautifully that Christian Liturgy ‘transforms and empowers when the vulnerability of human pathos is met by the ethos of God’s vulnerability in word and sacrament’ (Worship as Theology, 22).

Saliers notes the difficulty, due to today’s cultural pressures, in distinguishing ‘between immediacies of feeling and depth of emotion over time.’ Vital liturgy may produce ‘feeling states’ but that is not God’s criterion. Authentic liturgy needs time to deepen our ‘disposition to perceive the world as God’s creation’, to see and respond to the world through God’s eyes and with God’s heart. Gratitude, forgiveness, compassion, love and joy illuminate life with meaning in our head, heart and actions but only ‘unfold over time.’ They are not so much felt or produced but ‘elicited in season and out of season’, as with joy in time of tribulation (37).

What we can reasonably expect of liturgy, then, is not so much elation but devotion.

The peaceful and subdued joy of Easter Sunday is consonant with nourishing faith so that it is devoted, persevering and constant. For all that, Jesus himself still wants to ‘share his joy to the full’ (John 17:13). Again, Teilhard de Chardin rightly observes that ‘joy is the infallible sign of the presence of God.’

Finally, de Chardin has been a refreshing guide in these reflections. Appropriate for today, I close with this Wikipedia account of his death in New York.

On March 15, 1955, at the house of his diplomat cousin Jean de Lagarde, Teilhard told friends he hoped he would die on Easter Sunday. On the Easter Sunday evening of April 10, 1955, during an animated discussion at the apartment of Rhoda de Terra, with his personal assistant since 1949, the 73-year-old priest suffered a heart attack; regaining consciousness for a moment, he died a few minutes later. He was buried in the cemetery for the New York Province of the Jesuits at the Jesuit novitiate, St. Andrew’s-on-the-Hudson in Poughkeepsie, upstate New York.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)