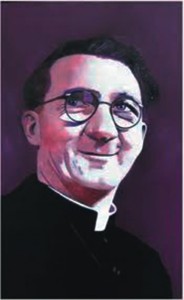

O’Flaherty – WWII Irish Priest Hero – ‘Pimpernel of the Vatican’

In Killarney National Park stands a grove of trees planted in 1994 to commemorate one of the town’s most courageous sons. Hugh O’Flaherty’s exploits during the Second World War earned him several commendations and resulted in two books and a movie portraying his life. Yet, fifty years after his death, he is still relatively unknown throughout the world.

Prior to Hugh’s birth in February 1898, his mother Margaret and father James were living in Killarney where James was stationed in the Royal Irish Constabulary. Margaret returned to her native Cork to give birth and shortly afterwards mother and son returned to Killarney. Hugh therefore considered himself a Kerryman to the bone.

James O’Flaherty left the RIC when Hugh was eleven years old and worked for the local golf club. As the family also lived on the premises Hugh spent a lot of time on the golf course and developed a passion for the game which never left him. Years later as a young priest in Rome, it would remain an important part of his life – he became Italy’s amateur champion despite a diocesan rule forbidding priests to play golf!

During his teenage years Hugh talked of the priesthood and at the age of twenty joined the Jesuit run Mungret College in Limerick. Two years later, under the sponsorship of the religious authorities in Cape Town, South Africa, he went to Rome to study. He attended the Propaganda College which was primarily for missionary training and it was here in December 1925, he was ordained. Over the next few years, he continued his studies and obtained Doctorates in Divinity, Philosophy and Canon Law.

For Hugh, 1934 was an eventful year. He became a Monsignor and Secretary to the Apostolic Delegate to Palestine, Monsignor Dini. Dini died shortly after arriving in the Middle East and Hugh stood in for him until later that year when he was again appointed Secretary – this time to the Apostolic Delegate to the Republics of Haiti and San Domingo. His gift of diplomacy was now being recognised and when he left there the Presidents of both islands decorated him for his work in famine relief. A two year post in Czechoslovakia followed before being recalled to Rome in 1938 for an appointment with the Holy Office.

The Holy Office dealt with all things relating to the Church and its doctrines, including decisions concerning miracles and visions. Hugh was the Scrittore or Writer, a position he held until after the war.

It was during this time that the gregarious Irishman became popular within Roman society. Although known for his boxing, hurling and handball skills, golf remained his first love in sports. He’d often be found on the golf course with people like Count Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law, and the former King Alfonso of Spain. Hugh’s popularity was not confined to sporting circles. He was invited to parties and functions attended by Rome’s most influential: royalty, politicians and celebrities of the day. While his social life caused some controversy in the Vatican, mixing with the rich and famous would stand him in good stead for the work he carried out during the war years.

Nine months after the start of the Second World War, Italy declared war on Britain and France. Benito Mussolini, Italy’s facist leader had signed a ‘Pact of Steel’ with Hitler earlier in 1939, securing an alliance with Germany.

Vatican City, however, would remain neutral, thanks to a treaty agreed by Mussolini and Cardinal Gasparri in 1929. In return for the Vatican’s political neutrality, it would become a city-state in its own right, subject to its own legal and monetary system, separate from the rest of Italy. Midway through the war, a white line was painted on the ground in front of St Peter’s Square as a clear indication of the Vatican City’s independence; it also meant that all protection for those living within the Holy See ended at that line.

The outbreak of war brought with it massive numbers of homeless and displaced persons. Prisoner of war camps sprung up all over Northern Italy and the Vatican took on the task of visiting the prisoners and looking after their welfare. Acting as secretary and interpreter, Hugh accompanied the Papal Nuncio Monsignor Bergoncini Duca. Setting out at Easter 1941, they would visit a camp a day, and when the Nuncio retired to his hotel, Hugh would take a train back to Rome, armed with the information he’d gathered during the day. Father Owen Snedden, a New Zealander, would broadcast these snippets on Vatican Radio along with the authorised scripts he was given. The two priests wanted the prisoners’ families to know as soon as possible that their loved ones were alive. Hugh would then return by train to be there for the next camp in the morning.

Over the following months, the young priest doled out thousands of books around the camps, including a prayer book he and another priest had made up, and he provided the prisoners with warm clothing for the onset of the cold Italian winter. He disregarded any regulations where the prisoners were disadvantaged, especially the bureaucracy involved in distribution of Red Cross parcels. At the end of 1942, under pressure from the Italian government, the Vatican recalled him to Rome and a new phase of his war work began.

The German and Italian authorities were combing the streets of Rome for ‘undesirables’, those opposed to the war and the country’s regime. Renowned anti-facists and Jews were particular targets – with many of whom Hugh had mixed at those pre-war parties. It was therefore inevitable that they should turn to him for help.

Frs John Flanagan & Owen Snedden with three Kiwi officers in St Peter’s Square in wartime Rome.The officer on the left is Capt V.P. O’Connell.

To begin with, he placed those in danger in the homes of trusted friends or in convents and monasteries, but as the situation worsened more drastic action was needed. Hugh then hid them in his own place of residence, ironically called the German College, due to the German nuns who taught there as well as the many German students attending. While not specifically within the Vatican City it was one of several buildings on the outskirts, under its jurisdiction.

People from all walks of life sought out the Irish priest: prisoners of war, Jews – almost 500 were hidden within the Vatican during the war – and Italian aristocracy. As the numbers increased the authorities put pressure on the Vatican to refuse further refugees claiming sanctuary within its walls. Once again Hugh was forced to look elsewhere for help, turning to some of the many contacts he had made over the years. One such place of hiding was an Italian police barracks where fourteen British prisoners of war were housed. This was one of the largest groups Hugh had helped at one time.

As the Irishman’s reputation grew, so did his contacts, and his working relationship with Cockney John May was to prove one of the most significant. The butler to the Vatican’s British Minister had as many connections as Hugh if not more, especially those involved with the Black Market! Between them they helped house, clothe and feed thousands who appealed for help throughout the war years.

Hugh O’Flaherty was certainly courageous as well as being blatantly fearless. He was hardly inconspicuous, being tall, having round-rimmed glasses, a scarlet and black cassock and wide brimmed hat, yet he freely visited his friends or hospitals and gathered provisions, raised funds, openly doing what he needed to do for the organisation. So it was only a matter of time before the Gestapo were alerted to his activities and after a near capture, he resorted to a disguise when walking Rome’s streets.

Most nights, under the watchful eyes of the Germans on the street below, the Monsignor would be found on the steps of St Peter’s saying prayers but on hand for anyone who approached him. A Jewish man, expecting that he and his wife would be arrested at any time, once asked him to care for his young son. He gave the priest a solid gold chain as payment for the child’s keep. Hugh hid the boy but obtained false papers for the couple, enabling them to remain in Rome; at the end of the war, parents, son and gold chain were reunited.

The risk taking continued, as did avoiding capture, with the Germans eventually giving him the nickname ‘The Pimpernel of the Vatican’. For one Nazi he became an obsession: Colonel Herbert Kappler was head of the Gestapo in Rome and was known for his brutality. He threatened the Jews of Rome with deportation to Germany if they did not hand over 50kg of gold which, with the Italians’ help, they did – 200 Jews were transported to the death camps anyway. The heightened security Kappler imposed put extra pressure on Hugh and his helpers.

The arrival of Royal Artillery officer Sam Derry saw Hugh’s resistance movement become more organised. The Dunkirk survivor became an integral part of the group, working mainly with the escaped prisoners of war, and handling the administrative duties. He kept a journal of those years which became a book called The Roman Escape Line, in 1960.

By early 1944 subterfuge and security had been stepped up. Hideouts were located, refugees arrested, torturing and shooting were rife. The movement had its work cut out, constantly relocating and seeking new places to shelter those in danger. The Vatican’s Pimpernel continued to avoid capture, much to the annoyance and frustration of Kappler.

A few months later, although the Germans knew their occupation of Rome was coming to an end they continued their reign of terror till the last. When the cheering crowds welcomed the Allies into the city on the 4th of June, the Nazis had all but gone.

Rome may have been liberated but for Monsignor O’Flaherty there was still much work to be done – only now it was the Italian fascists and Germans who were in need. ‘God has no country’ was his attitude. He visited prisoner of war camps, compiling information for tracking down families, and travelled to Jerusalem to organise immigration to Israel for the Jews he’d helped. He also flew to South Africa, setting up a network to trace Italian prisoners of war for relatives at home.

Even when relaxing Hugh’s radar for the underprivileged was working. He came across some destitute villagers living in their ruined surroundings near to a golf course where he was playing one day. In no time, he had organised food, clothing and furniture, as well as help to rebuild their houses and chapel. For many years afterwards he would celebrate Mass there every Sunday.

At the end of the war Hugh O’Flaherty received a CBE (Commander of the British Empire) and a US Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm. He was awarded a silver medal for valour from the Italian Government together with a pension for life – the latter of which he refused. In 1953 he was made a Domestic Prelate, a title given by the Pope to a priest for exceptional work, and several years later he became Head Notary of the Holy See.

Colonel Herbert Kappler was sentenced to life imprisonment for war crimes and his only monthly visitor was Monsignor O’Flaherty. In 1959 the former Gestapo officer was baptised into the Catholic Church by the Monsignor himself.

In June 1960 Hugh suffered his first stroke and three months later returned to Ireland to live with his sister Bridie and her husband in Cahersiveen, in County Kerry. Since the war ended he had refused to talk about his activities during that time – except once. His failing health had prevented him being the focus of an episode of This is Your Life so the episode that aired in February 1963 featured Sam Derry. Hugh was flown in as a surprise guest and the two men met for the final time. On the 30th of October 1963 he died at home.

It’s not known how many lives were helped and saved by Hugh O’Flaherty and his organisation, though it’s believed to be in excess of 6,000. Sam Derry’s detailed records account for almost 4,000 but that doesn’t include the many hundreds of Jews and Italians helped by the Monsignor. In 1983 the film The Scarlet and the Black with Gregory Peck as Hugh O’Flaherty brought this extraordinary Irishman’s story to life.

Perhaps it’s time to remind the world again about this humanitarian who couldn’t say ‘no’ to a soul in need, regardless of race, colour or creed.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)