God, Evil and the Boxing Day Tsunami?

The huge earthquake off the coast of Indonesia and subsequent enormous tsunami occurred on Boxing Day 2004. The total loss of life in this event, mainly from the tsunami which swept across the Indian Ocean as far as the coast of Africa, was in excess of 250,000 people.

Since December 2004 there have been many other disastrous earthquakes and tsunamis, particularly in the last couple of years – Peru 2007, Samoa 2009, Indonesia again in 2010, Haiti in 2010, Chile 2010, Christchurch 2011, Japan 2011. It seems that the so-called ‘Pacific Ring of Fire’ is very active at present.

There are multiple examples in Scripture assuring us that God loves us, cares for us, and protects us from evil. A few minutes with a searchable Bible on a computer (eg bible.oremus.org) using keywords such as watch–over, protect, loving kindness, caring, brings up multiple references. So each time a natural disaster with large loss of life occurs one is driven to ask again and again what was God doing.

It is an important facet of Christian belief that not only did God create the universe in all its enormity but also sustains it in existence continuously. Given this, we are led to wonder how it can be that such natural disasters claim so many lives. Is God momentarily looking the other way?

The so-called ‘problem of evil’ comes in two forms. Moral evil which is evil perpetuated by human beings – Nazis and the Holocaust, Pol Pot, Ruanda etc. These atrocities are committed by free (although possibly demented in some way) human beings, so there is no need to blame God. However, for natural evil, due to the forces of nature, of which earthquakes, tsunamis, tornadoes, floods are examples, there appears to be no apparent explanation other than to blame God.

Much ink has been expended in attempting to find a convincing solution to the problem of natural evil. Despite these efforts the fruits are meagre. In fact, this question is so pressing that it is commonly offered as a justification for agnosticism and atheism. People will say that without a coherent answer to this question they will have nothing to do with the Christian faith and its understanding of a loving God. One could respond by saying that such a stance is rather arrogant – it entrusts human reason with too much authority – but, even so, one can appreciate the perplexity behind the stance.

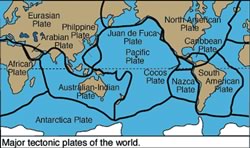

Deepening scientific awareness in the twentieth century led to revolutions in our perception of the planet earth. In the 1960’s pictures taken from within the lunar orbit during the Apollo programme revealed the stunning beauty of the earth and also convey a sense that it operates within a delicate balance. Very clear from these images are the boundaries between the continents. In the 1920’s a German meteorologist named Alfred Wegener (1880-1930) proposed that the continents are moving slowly across the surface of our planet having originally been part of one large super-continent called Gondwanaland. At the time Wegener was laughed out of court. But during the 60s several independent strands of geophysical evidence came together to confirm the drifting continents theory and so was born what we now call plate tectonics. Given the present wide separation of the continents it is apparent that there have been enormous changes in the surface of the earth since the time of Gondwanaland.

I find it helpful to view the problem of natural evil from within this understanding of the geological and geophysical processes at work within and on the surface of our planet. New Zealand sits astride the boundary between the Pacific and Australian plates. Each year there is a relative movement of about 40 to 50 mm (one and a half to two inches if you are that way inclined) across this boundary. There is abundant evidence that most earthquakes, and certainly those around the Pacific Rim, are associated with plate boundaries. Now if the relative movement across plate boundaries is a few tens of millimetres per year it must have taken a very long time for the evolution of the planet to move the continents to their present positions from the original Gondwanaland. Current estimates place the age of the earth at about 6 billion years, so there has indeed been plenty of time to allow these slow changes in the earth’s surface to accumulate.

...we participate in this coming into being of the earth, the whole of creation for that matter

In the Letter to the Romans, Paul speaks of the whole of creation groaning with labour pains. I think of this long drawn out process of continental drift as a facet of these labour pains. Paul, of course, can have had no understanding of how long this groaning had been taking place. It is also apparent from his writings that he had no idea of how long it would continue into the future. Insignificant is the span of a human life in relation to the time this groaning of creation has been taking place. We view only for a fleeting instant something far beyond and bigger than anything we can perceive, but, even so, we participate in this coming into being of the earth, the whole of creation for that matter, but are unable to appreciate the true scope of what is happening.

So what are we to make of the biblical references indicating that we are protected – for example the sparrow sayings of Jesus in Matthew and Luke? Suffering is part of human experience, and I think part of the groaning that St Paul mentions. Furthermore, I like to think of natural disasters as episodes in the groaning of our planet. So, I wonder if what the biblical passages are assuring us is that our “why?”, unanswered at present, will eventually be resolved in a way that shows how our individual sufferings and lives and deaths contribute to the cosmic working out of creation coming fully into being. In other, words what we are involved in, only for a comparatively very brief time, is something far greater than we can ever begin to understand now, but, our tiny part in it will not be in vain. A quote from Teilhard de Chardin, used in a recent Tui Motu editorial, “Above all, trust in the slow work of God”, says it nicely.

Michael Pender is a Professor of Geo-Technical Engineering at Auckland University, NZ, and parishioner of St Michael’s parish, Remuera Auckland.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)