October Saint

Fr Mervyn Duffy SM

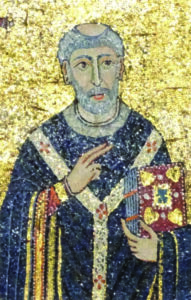

St Callistus

While studying in Rome, I kept coming across the name of Pope Callistus. The catacomb that bears his name was a standard tourist destination and one of my favourite churches, Santa Maria in Trastevere, has his remains buried beneath the altar. The original church on the site may have been built when he was Pope because its earliest name was “Titulus Callisti”.

While studying in Rome, I kept coming across the name of Pope Callistus. The catacomb that bears his name was a standard tourist destination and one of my favourite churches, Santa Maria in Trastevere, has his remains buried beneath the altar. The original church on the site may have been built when he was Pope because its earliest name was “Titulus Callisti”.

Callistus was the sixteenth Pope, holding the office for five years in the early part of the third century (217-22 AD), during the period when Christianity was an illegal and sometimes persecuted religion. His story, what we can reconstruct of it, is remarkable.

He was of Greek birth, and first appears in the historical record as a young slave in Rome owned by a Christian called Carpophorus. He must have been intelligent and well-educated because Carpophorus put him in charge of the funds of the Church community. The small Christian community was concerned with looking after its own poor, widows and orphans and raised money for this purpose. Investing then, as now, was a risky business and Callistus lost the monies he had been entrusted with. He was rightly worried that Carpophorus would punish him, so he fled and was trying to take ship from the port at the mouth of the Tiber when he was captured (despite jumping overboard). Taken back to his master, he was imprisoned then released on the understanding that he was to recover the lost investment.

The tomb of St Cecelia in the Catacomb of St Callistus

The missing money had been lent to Jewish businessmen and his attempt to convince them to return it resulted in a brawl in a synagogue. Callistus was arrested by the Roman authorities and sentenced to the mines in Sardinia. When he was freed from this (and from slavery) he was in such bad shape that Pope Victor provided him with a sickness benefit. He must have recovered his health and his status in the Christian community because in 199 AD he was ordained by Victor’s successor, Pope Zephyrinus, as a deacon and put in charge of the catacomb on the Appian Way now named for him. Again he must have shown himself to be an able administrator and holy man because when Zephyrinus died it was Callistus who was elected to succeed him as Pope.

The pontificate of Callistus was characterised by mercy and charity. He taught that repentant sinners, even those who had committed grave sins like adultery and murder, could be readmitted to communion if they repented and did penance. He argued that power to bind and to loose had been given to St Peter, and as the successor of Peter he could grant such absolution. Hard-line contemporaries, like Tertullian and Hippolytus, thought Callistus was “soft on sin” and argued that the power had been given only to Peter personally. Thanks to St Callistus the merciful view prevailed, and the verse about binding and loosing can be seen in letters two metres high running around the interior walls of St Peter’s Basilica.

How St Callistus came to be martyred is unclear. He may have been killed in a riot. According to legend, he was tied to a stone and dropped down a well.  There is a church of San Callisto built over a well which claims to be the spot where he died, and in Santa Maria in Trastevere there is a spherical column decoration with a Latin inscription attesting that it is the stone that was attached to Callistus.

There is a church of San Callisto built over a well which claims to be the spot where he died, and in Santa Maria in Trastevere there is a spherical column decoration with a Latin inscription attesting that it is the stone that was attached to Callistus.

On 14 October we honour the slave who became Pope and made our Church a more merciful institution.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)