Words and God’s Word

By Fr Tom Ryan SM

Part 1 of 10

Sticks and stones will break my bones but words will never hurt me.

We know that jingle. It might trigger a memory of mum or dad using it to reassure us. Perhaps they were helping us build up some personal armour against schoolyard teasing or verbal bullying.

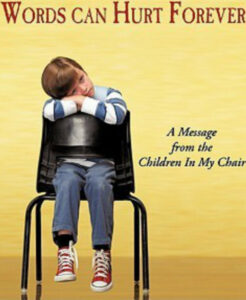

But life experience, and checking out social media platforms or Google, suggests the reverse: “sticks and stones will break my bones but words will (often) hurt me.” It’s true. Words can harm, can wound, can leave scars -- even life-long, especially when combined with images.

Think of schoolyard nicknames, especially those aimed at physical traits or bodily shape. How many people hesitate to sign up for a school reunion? In seeing classmates after some years, amidst the mists of unrecognised faces, someone’s eyes light up in front of me. And the first thing they say is that name—what I was called in the schoolyard or, more recently, on Twitter or Facebook. We’re both still locked in the past. Who wants to go back there? Understandably, school reunions get a wide berth.

Think of schoolyard nicknames, especially those aimed at physical traits or bodily shape. How many people hesitate to sign up for a school reunion? In seeing classmates after some years, amidst the mists of unrecognised faces, someone’s eyes light up in front of me. And the first thing they say is that name—what I was called in the schoolyard or, more recently, on Twitter or Facebook. We’re both still locked in the past. Who wants to go back there? Understandably, school reunions get a wide berth.

Again, there are changed attitudes to the sticks and stones of corporal punishment. Still, we are left with words -- the sneering putdown, an adult’s sarcasm, the student humiliated in front of the class. Such words can always hurt, even years later—their echoes shaping a person’s sense of who they are.

On the other hand, words can alter a person’s life for the better: the staff member who encouraged the struggling pupil; the form teacher, sensing family problems, overlooked the missed homework or glimpsed talent in a self-conscious teenager; the parent who affirmed effort in the midst of mistakes or failure.

Words, then, can build up or knock down. As tools of power, they have two faces. Words can be positive -- a force for good when used to seek what is true -- and are at the service of the well-being of a person or a community. Words can also be negative, used to deceive or demean, for selfish aims rather than the good of others.

Words, then, can build up or knock down. As tools of power, they have two faces. Words can be positive -- a force for good when used to seek what is true -- and are at the service of the well-being of a person or a community. Words can also be negative, used to deceive or demean, for selfish aims rather than the good of others.

Words -- Divine and Life-Giving

Words, then, can heal or hurt, can reveal or conceal, can be vehicles of truth or tools of deception. Most importantly, they can be life-giving. In that sense, they continue the action of God’s word.

Take the first Creation account in the Book of Genesis. We are told that God’s spirit hovered over the ‘water’ (‘formless void’) or chaos. But it is not from God’s spirit that creation (cosmos or order) comes. It is from God’s word: “God said, ‘Let there be light’, and there was light.” Once that is done, it is the Divine spirit that animates and sustains creation.

This is God’s creative presence at work. We use the analogy of human language to capture this. What is a word? It is a breath with ‘skin on.’ Without our breathing we cannot say a word. God’s creative act needs both word and breath. It is with Jesus we see the full significance of this -- more on that later.

But there is another aspect at work here. We can speak of words that are informative and of those that are performative. “Auckland is a city in New Zealand.” Facts are communicated here. This is informative speech.

But what about when we hear: “I declare this building open” OR “I baptise you in the name of…” OR “I sentence you to thirty days community service.”

But what about when we hear: “I declare this building open” OR “I baptise you in the name of…” OR “I sentence you to thirty days community service.”

In speaking such words, we carry out a certain action and exhibit a certain level of power. These words are performative. For instance, in the Liturgy of the Word, when we acknowledge who we are -- sinners needing to be saved -- we move to being more open to God, to a greater sensitivity of conscience, to be better formed in truth and love. We allow God’s power to work, in other words, to change us.

We need to keep in mind two things. Scripture as God’s ‘word’ is not just statements or stories that are read and heard. It is the person of the Word who is present and communicating.

Second, the Hebrew understanding of ‘word’ embraces more than something expressed in speech or in writing. It is dynamic and performative -- it brings into reality what it conveys. As Pope Benedict notes, the Gospel is not about information, or, even, just about knowledge. Rather, the Gospel “makes things happen and is life-changing” (Spe Salvi, 2). It is a force whose goal is to make a difference -- in all of us.

So, too, with words, in everyday life. They are forms of power; they can bring about change—for better or for worse.

So, too, with words, in everyday life. They are forms of power; they can bring about change—for better or for worse.

How that is the case? What light can our human experience together with God’s word in the Scriptures throw on ‘words’ and how we use them? That is what this series will be about.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)