“For You Were Strangers In The Land of Egypt”

Five years ago, I visited the UK during the Brexit campaign. It was an interesting time to be there. However, for me, the historic importance of the vote’s outcome was overshadowed by a chance meeting the day after.

I was leaning on the railing along the promenade of a south coast town, stoically enjoying the cold, grey, drizzly summer’s day, watching the waves break on the stony beach, when a young man suddenly appeared beside me. He was silently waving a piece of paper in one hand while pointing at it with the other. Aware that no one else was around, I wasn’t sure just what to prepare myself for.

However, I needn’t have worried. With his gestures and handful of English, he asked me to tell him what was in the letter. It was from the government informing him that his benefit had been approved and what he needed to do next. His name was Ali.

It’s very difficult to mime an official letter and just as difficult to tell him that I wasn’t a local and probably not the best person to help him. But I did attempt to find out a little about him and he produced another letter that said he’d been granted refugee status.

I managed to discover that he was Iranian, eighteen, and had made it to the refugee camp in Calais after walking and hitch-hiking on his own for over two years. He’d then managed to get to England on the axle of a truck and was now living alone in a flat in this tired seaside town.

I managed to discover that he was Iranian, eighteen, and had made it to the refugee camp in Calais after walking and hitch-hiking on his own for over two years. He’d then managed to get to England on the axle of a truck and was now living alone in a flat in this tired seaside town.

We conversed in our strange way until the rain arrived and we parted, but I often think about him and wonder how he’s coping and if I could have better helped him.

By the end of 2019 there were 79.5 million displaced people worldwide. Nearly 26 million of them were refugees, around half of whom were under eighteen. There are many, many Alis out there.

In their desperation, many migrants fall into the hands of traffickers who exploit them and subject them to physical and psychological abuse. Many end up in inhumane detention camps, including in our part of the world. And many die.

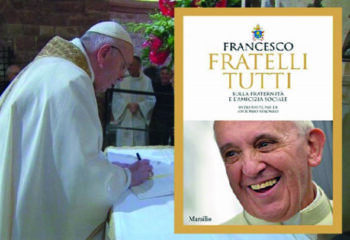

Pope Francis discusses the plight of those fleeing war and persecution or searching for a better life for themselves and their families in his latest Encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship.

He also notes that those who do eventually make it to safety aren’t necessarily welcomed. Many forget that refugees “possess the same intrinsic dignity as any person.” By our decisions and the way some treat them, “we can show that we consider them less worthy, less important, less human” (Fratelli

He also notes that those who do eventually make it to safety aren’t necessarily welcomed. Many forget that refugees “possess the same intrinsic dignity as any person.” By our decisions and the way some treat them, “we can show that we consider them less worthy, less important, less human” (Fratelli

Tutti, # 39).

“For Christians, this way of thinking and acting is unacceptable, since it sets certain political preferences above deep convictions of our faith: the inalienable dignity of each human person regardless of origin, race or religion, and the supreme law of fraternal love” (# 39).

Unfortunately, the sense that we belong to a single human family seems to be morphing into indifference. It seems to me that we’re losing sight of the fact that we’re all in the same boat, a boat that’s in grave danger of overturning.

Pope Francis points out that even in the oldest texts of the Bible, such as Exodus 22:21, we can see why we should embrace migrants. And, similarly, in Leviticus: When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not do him wrong. The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the stranger as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt (19:33-34).

He notes that in the New Testament, the parable of the Good Samaritan shows us how, by identifying with others’ vulnerabilities, we can reject exclusion and act instead as good neighbours (# 67).

“There is a problem when doubts and fears condition our way of thinking and acting to the point of making us intolerant, closed and perhaps even – without realising it – racist. In this way, fear deprives us of the desire and the ability to encounter the other” (# 41). Good neighbours develop an openness to others.

In an ideal world there would be no refugees, but we are not there yet and Pope Francis reminds us that our response must be “welcome, protect, promote and integrate." He says that we need to work together through these four actions, while preserving our respective cultural and religious identities, being open to differences and knowing how to promote them in the spirit of fraternity (# 129).

He gives many practical examples of how we can support this, for example by simplifying the granting of visas; adopting programmes of individual and community sponsorship; providing suitable and dignified housing; guaranteeing personal security and access to basic services; equitable access to the justice system; guarantee of the minimum needed to survive; the possibility of employment; protecting minors and ensuring their access to education; guaranteeing religious freedom; promoting integration into society; supporting the reuniting of families; and preparing local communities for the process of integration (# 130).

I think often of Ali and pray that he’s been able to establish a meaningful life for himself in the UK. I remember, too, that Jesus was a refugee for a period when his family fled to Egypt to avoid persecution. And I reflect on the fact that we are all immigrants or the descendants of immigrants who, over the last 700 or so years, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand seeking a better life.

While our borders may be closed for the moment, we can still open our hearts to those who have newly-found refuge here and are now ‘us;’ and we can pray for peace for all those still seeking refuge and for those working to build a more humane and just world for all.

Reprinted from Stories of Hope, Our Lady of Hope Parish, Titahi Bay and Tawa. Used with permission.

The Day of Prayer for Refugees and Migrants is Sunday 6 June.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)