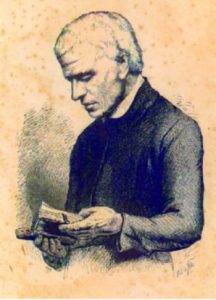

Fr Jean Baptiste Petitjean SM ‘Parish Priest to all New Zealand’

Part 2 of 3

On 11 December 1841, Fr Jean-Baptiste Petitjean wrote to the founder of the Marist order, Fr Jean-Claude Colin, from Kororāreka in The Bay of Islands. In his letter Fr Petitjean recalled his first days as a Marist missionary. “I was then just a young conscript facing his first battle, and now that I am somewhat hardened, I do not let myself get so easily disconcerted”.

Two years after his arrival in New Zealand in December 1839, Fr Petitjean was relishing the challenges and privations of missionary life. Still only 30 years old, in his letters home he delighted in recounting his adventures in the mission field: “I rest on a bed of brushwood, or more softly still, on the sand, without fearing that the noise of the waves will trouble my peaceful sleep... here the ground is my seat and my table; little baskets made of large leaves serve instead of plates and dishes”.

Oceania was one of the last frontiers in the world for evangelisation. Fr Petitjean was both awed by this, and grateful to be an “instrument in this day of salvation”. As he wrote to Fr Colin, “When I walk alone on the seashore, I ask of these waves... how often they have broken on these coasts without bringing to them their apostles; and I cannot refrain from groaning”.

In the far north, where Fr Petitjean was stationed, the main centres of missionary activity under Bishop Pompallier were the Hokianga, the Bay of Islands, Kaipara and Whangaroa. Based in Kororāreka, Fr Petitjean travelled throughout the north in his work of evangelisation and cultural encounter. He quickly became fluent in both Māori and English. But it was profound differences of culture rather than language which posed the greatest challenges.

Writing from the Bay of Islands in May 1842, Fr Petitjean described his inadvertent violation of tapu. In Whangaroa he had built a shelter, and placed his hearth a short distance from a former burial site.

The incident came close to provoking violence, but was peacefully resolved. In the course of a heated argument -- conducted entirely in Māori, a tribute to his fluency -- Fr Petitjean offered reassurances of Catholicism’s respect for the dead and their resting place. Such flashpoints of tension were not uncommon in the meeting of two profoundly different cultures.

In 1841, Fr Petitjean wrote of how he baptised a gravely ill young boy. He gives a touching description of how he sat talking with the boy’s father, explaining the meaning of baptism, before at last being given permission to administer the sacrament with water that had accumulated after a recent fall of rain.

If Jean Baptiste Petitjean and his fellow missionaries were filled with zeal, they often lived in great material poverty. In his history of New Zealand Catholics, Michael King quotes a writer who encountered a missionary on Papamoa Beach in 1842: “I never remember seeing a more miserable figure - travel worn, unshaven and unwashed… on his back a kind of sack containing in all probability all he possessed in the world”. For many Māori, the poverty of the missionaries was something of a puzzle. Fr Petitjean noted this fact in one of his letters, “...ministers of the Catholic religion… are, in their eyes, powerful and rich chiefs. The New Zealanders have trouble understanding how it could possibly be otherwise when it comes to spiritual authority”.

In October 1842, Fr Petitjean’s missionary work among the Māori people of the north came to an end when he was appointed Auckland’s first parish priest. In the wake of the Treaty of Waitangi, Auckland, along with the rest of New Zealand, had a rapidly growing population of European settlers. Among them were many Catholics, mainly of Irish origin.

These European Catholics keenly felt the lack of priests in the colony, and during this period there was no one but the French Marists who could minister to their needs. The Marist missions had not been geared towards the kind of parish ministry which rapidly changing circumstances made a necessity.

For Fr Petitjean, leaving the Māori mission was a painful disappointment. “I was”, he later wrote, “inconsolable at the loss of my dear Māoris”. He recognised, however, that a missionary must be “prepared to occupy any post… to conform his will continually to the Will of God and that of his superiors”.

By January 1843, a church had been opened at the new Auckland mission station. This church also served as a schoolroom, and had a roll of 155 pupils by 1845. Auckland’s Catholic population continued to grow, bolstered by soldiers recruited in Ireland who were brought in to protect the fledgling town. By 1848, the first St Patrick’s Cathedral -- a new church was built on the site in 1907 -- had been consecrated.

Despite his initial disappointment, Fr Petitjean found fulfilment in his new role: “... how much it would cost me to leave Auckland! … the little children of my school are my delight; the Irish rejoice me by their wonderful faith”.

He was a man who quickly formed enduring emotional attachments. To be ready always to move on to the next place to which he might be sent was unusually hard for a man of his temperament. Fr Petitjean recognised this in himself, trying hard to cultivate what he termed, “Holy indifference”: “To what will not my poor heart attach itself?”, he asked, while reflecting on his life in Auckland. A few years later, in 1850 he was to be uprooted again, and sent south to Wellington, where he would at last find a permanent home.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)