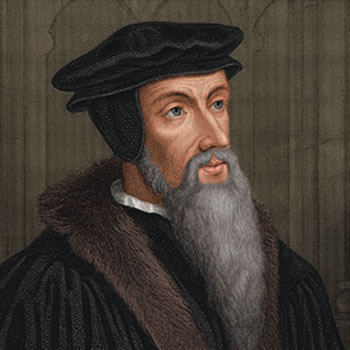

Mary and the Reformation (7) – John Calvin (1509 – 1564) Part 2

Br Kieran Fenn

True praise of Mary

John Clavin

Christian praise is praise of God. Yet Calvin was not against praising Mary if it was done in the right way: “Let us learn to praise the holy Virgin. But how? By going along with the Holy Spirit, and then there will be true praise.” Mary herself recognised that, mere ‘servant of the Lord’ that she was, she was “chosen by God before she was born, even before the creation, and numbered among God’s own, and not as though she had come to God by her own motion.” In the inspired words of Elizabeth, “it is the Holy Spirit who proclaims Mary blessed because she believed, and in praising Mary’s faith generally teaches us where true human happiness is located.” So, Mary is an object of admiration, praise, and imitation.

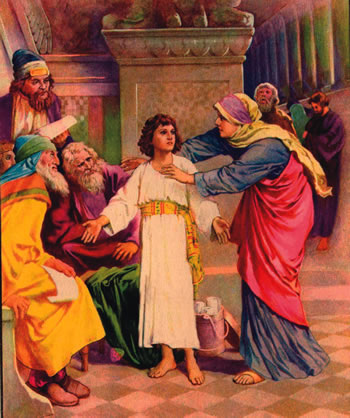

Calvin disagreed with those who ascribed sinful pride to her when she asked her twelve-year-old child why he lingered on behind in Jerusalem. “She was not pushed by any pride, but this query was prompted by three days of sorrow.” While his parents knew something of his heavenly origins, they did not yet understand the true nature of his mission. The fact that she kept in her heart what her mind did not yet understand, places Mary in the mystical tradition. The faithful, like her, should ponder deeply what God has done for them.

Calvin disagreed with those who ascribed sinful pride to her when she asked her twelve-year-old child why he lingered on behind in Jerusalem. “She was not pushed by any pride, but this query was prompted by three days of sorrow.” While his parents knew something of his heavenly origins, they did not yet understand the true nature of his mission. The fact that she kept in her heart what her mind did not yet understand, places Mary in the mystical tradition. The faithful, like her, should ponder deeply what God has done for them.

The Annunciation

At the Annunciation, Mary was “a good teacher, provided we learn at her school as is fitting: Let us ask that it be done unto us according to the word of God.” She was “a mirror of the faith that we must bring to our God.” When she kept ‘words in her heart,’ it was not for herself alone, but for future times: “She brings to us our Lord Jesus Christ. This is the honour that God has given her; this is how we must look at her: not so as to stop at her, or to make her an idol, but that, by means of her, we be led to our Lord Jesus Christ, for it is there also that she sends us.”

The Word of God should be welcome in our heart “according to the example of the holy Virgin, that each one should conform to the respect she showed for the Word of God.” Calvin often translated the biblical image of the Virgin Mary into examples of a holy life, of a model for faith, obedience to God, thanksgiving for Christ, listening to the Word of God, following the Holy Spirit, praising God, and of personally witnessing to God and Christ.

The ‘infernal abyss of the papacy’

Calvin was relentless in his attacks on Roman interpretation of the Marian texts of Scripture as “idolaters who make an idol of Mary and ascribe to her what belongs to God alone.”

“The papists ascribe to her titles that belong to God. They call the Virgin Mary ‘Queen of heaven, Star to guide poor errant folk, Salvation of the world, Hope and Light.’ God appropriates nothing in Scripture that is not transposed to Mary by papists. They even call Mary ‘our Advocate,’ a term which in the New Testament designates Christ or the Holy Spirit.” Calvin’s protest is well formulated in his sermon on Luke 2:15-19, the Shepherds at the Crib: “The papists call the Virgin Mary Treasurer of grace, and in blaspheming God they give her a frivolous and imaginary title, for they would like her to hold the office of our Lord Jesus, which is to extend to us all the goods that have been given him by the Father in order to share them with each of the members of his body as he pleases and as is fitting.”

Addressing prayer to others rather than God was anathema to Calvin; to make creatures hold divine power and authority is the essence of idolatry. He found irony in that the Assumption prevented the papists from advertising relics of her.

Sobriety

![]()

Calvin saw the holy Virgin as picture, a special example of faith, an icon of true discipleship. This is Mary in relation to the soul. The Church’s mothering of the faithful is imaged in Mary’s mothering of Jesus. The generations that followed Calvin lost the positive aspects of Calvin’s perspectives on Mary.

Source: Tavard, George H., The Thousand Faces of Mary, Michael Glazier, 1996.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)