Martin Luther

Fr Tom Ryan sm

The 500th Anniversary of the Beginning of the Reformation

Lutherans celebrate Reformation Day annually on October 31. That day in 2017 will mark the 500th anniversary of the start of the Reformation - when Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses on All Saints Church door in Wittenberg, Germany.

In October 2016, Pope Francis participated in a joint Lutheran-Catholic service in Sweden to mark the start of a year marking this anniversary. The Pope said this commemoration of the beginning of the Reformation must take place in a spirit of dialogue and humility. This sets the tone of the following thoughts.

On that October day in 1517, Martin Luther, Augustinian monk and gifted teacher, almost certainly had little idea what would eventually happen to the Church and to Europe. His concerns were justified: a focus on incidentals (indulgences to raise money) rather than on God’s grace and Gospel simplicity; renewal of the priesthood, governance and the Church’s mission to nourish the faith and devotion of ordinary people.

For at least a century, others had raised similar concerns. It was a call for the Church to be what it should be. By 1517, Luther’s words and action summed up what many thought and felt. The image sometimes used to capture this is a bonfire. It’s twigs and wood were tinder dry. It only needed a spark. Along came Luther.

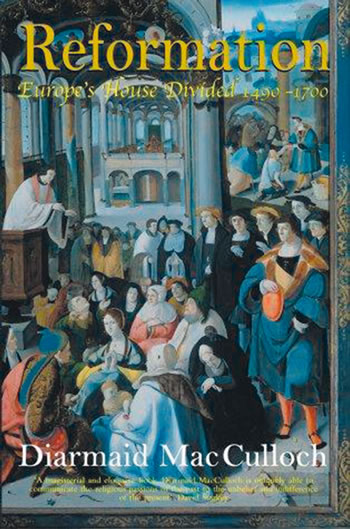

Today, historians such as Diarmaid MacCulloch, still try to understand what happened and why. His book captures it: Reformation: Europe’s House Divided. This title distils the religious and political upheavals that occurred and the Catholic and Protestant responses.

While Luther started the fire, other figures (Church, secular, political rulers) provided the momentum and direction of what eventually happened. At times, Luther felt pushed into a corner, at others, he was stubborn, even misguided, sometimes plain wrong. Some events shocked him. Again, he was anti-Semitic.

With Luther and others, things could have been handled differently. Pope Francis perhaps alludes to this: ‘Catholics and Lutherans can ask forgiveness for the harm they have caused one another and for their offences committed in the sight of God.’

Luther retained a life-long sense that we are all both justified and sinners, including himself. What can we learn from Martin Luther looking back 500 years?

First, to follow Christ is not to be carried along with the crowd or by the Church. It must be based on a personal response to Jesus Christ. Yes, Jesus is our crucified and risen Saviour. But if he is not ‘crucified and risen’ to save me, then, faith will be superficial, a house built on sand.

So, for Luther, faith must be a personal choice and commitment. Further, we believe what Jesus tells us about God and life because we believe in Him. Faith starts with trust from within a personal relationship. In this, Luther and Thomas Aquinas agree.

Christ in the Wilderness

Ivan Kramskoy

Second, Luther rediscovered the Bible. God’s word is embodied in God’s Word present in the Sacred Scriptures. While Luther retained the Eucharist, the Scriptures are the main ‘food’ to nourish our minds and hearts. As St Jerome said ‘to be ignorant of the Scriptures, is be ignorant of Christ.’

Luther’s teaching started here. On this, he and Aquinas again agree. The principal source for Aquinas’ day-to-day teaching was the Sacra Pagina – the Sacred Scriptures. Interestingly, if Aquinas was teaching in the lecture room next to Martin Luther, they would both have been expounding and commenting on the Scriptures.

Third, Martin Luther reminds us how ‘the cross puts everything to the test.’ There are times, as Alister McGrath says, when ‘we cannot grasp God fully; we are walking in the dark, rather than in the light; our grip on reality is only partial and deeply ambivalent; we are assaulted by temptation, doubt, despair’ (The Passionate Intellect, p60).

C S Lewis

For example, take CS Lewis, who, when his wife died, tried to make sense of his overwhelming grief and suffering.

He turned to God and found the door slammed in his face ‘and a sound of bolting and double bolting on the inside. After that, silence’ (CS Lewis, A Grief Observed, pp 6-7). This impelled him to theology, as Luther suggests, done at ‘the foot of the Cross’ before he, finally, arrived at a sense of peace.

Luther’s point is that we do not walk alone. We are accompanied by the One who suffered and died for us and who will never abandon us. ‘The cross, like Mount Sinai, may be enfolded by clouds and darkness. Yet God remains present in this darkness, transcending both our capacity to discern him and our willingness to trust him’ (McGrath, p64).

To conclude, Jesus Christ Our Saviour was the centre of Martin Luther’s life and faith.

We can all learn from such a legacy -- whatever our differences.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)