Mary and the Reformation (1) – Erasmus

by Br Kieran Fenn FMS

500 years ago

Many things contributed to the breaking up of the Catholic

Mary, Stella Maris, Star of the Sea

Christian world of the Middle Ages: the Hundred Years War, the Black Death, the Western Schism, and the Islamic invasions. Humanism found a warm reception in Rome with the popes of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, all worldly men more interested in the arts and their own pleasures than in religion.

As our focus is Mary and the Reformation, the natural starting point is the attitude to the Blessed Virgin of Erasmus of Rotterdam (d.1536), a man who was friend to both Saints Thomas More and John Fisher.

In his early years Erasmus fully shared the Catholic Marian devotion of his time, calling her our only hope in our calamities and composing a Liturgy of the Virgin of Loreto. As he began to study the Bible and the Fathers of the church more carefully and came into contact with the popular abuses of his time his tone changed. He reacted violently to the external practices that only too often took the place of true religion in that era of decline. He poured out his sarcasm on the prevalent superstitions. In The Shipwreck, sailors called on the Star of the Sea, Queen of Heaven, Mistress of the World, Port of Salvation, and many other flattering titles which Holy Scripture nowhere applies to her. He asked, what does Mary have to do with the sea, since she appears never to have sailed on it?

Centrality of Christ

Erasmus wanted to see Christ once more at the centre of Catholicism, and the moral law reinstated in the place of merely external practices. He was not opposed to Marian shrines, having visited Walsingham twice in 1512 and 1514. But he wanted to combat the superstitious idea that a vow would not be valid unless it was attached to a place where the Virgin was venerated. He blamed the Christians of his day for never seeming to address themselves to God, but only to Our Lady and the saints, when they were in danger.

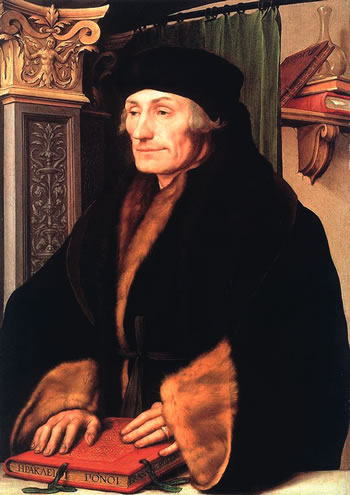

Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1523,

by Hans Holbein the Younger

In the Pilgrimage for Devotion Erasmus attacked the idea, so common then, that Jesus can deny his mother anything. It is written as a letter from Mary, in which she says how glad she is that Luther put a stop to streams of prayer to her asking for inappropriate favours: a businessman on a journey entrusting to Mary the faithfulness of his concubine; robbers asking for a rich haul; a prostitute asking for wealthy customers, and priests asking for promotion to rich parishes. If she refuses, then she is not mother of mercy. Erasmus attacked an external devotion devoid of any truly religious and moral content. R. Laurentin, a prominent writer on Mary, stated, ‘One can only shudder to see the miserable situation in which Marian devotion found itself when the Protestant crisis broke out.’

Erasmus complained that those who opposed the exaggerations of Marian devotion were immediately suspected of heresy. He himself was only against the constant invocation of Mary and the complete absence of prayer to the Holy Spirit. He can hardly be blamed for criticising those who are devout to the Blessed Virgin with images, candles and chants, but defy Christ by impious lives, thinking that by singing the Salve Regina, which they do not even understand, to gain her favour, then offend her by spending their nights in obscenities.

Linguist and scholar

St Thomas More, 1527,

Hans Holbein the Younger

Erasmus was a fine biblical scholar who went beyond the Vulgate to the Greek original. Thus, he translated ‘full of grace’ in its truer meaning as ‘being in favour’ with God, a translation now accepted. Mary’s ‘lowliness’ is recognised ahead of ‘humility’ in the Magnificat. Theologians could well be guided by linguists, he said, a truth more easily accepted today than in his own times. Further exaggerations were criticised by Erasmus, such as attributing to Mary the Beatific Vision, the direct vision of God, in this life; and that Christ had to obey her because she is his mother. How can this be, Erasmus asked, since even a father has no power over a human son who holds an office of authority in the State or Church, and grown-up sons have authority to enter marriage or religious life without the consent of their parents?

It is undeniable that Erasmus was justified in his opposition to the idea that even the risen Christ reigning in heaven is subject to his human mother, an idea widely held in the later Middle Ages. Apart from a few of his earlier writings Erasmus never spoke against the Mother of God except to criticise the excesses of devotion to her. Though he remained a Catholic throughout his life, his insights and work in Scripture and on Mary played into the hands of the Reformers who owed many of their arguments to him.

Source:

Graef H & Thompson T, Mary: A History of Doctrine and Devotion, Ave Maria Press, 2009

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)