Stories of Mercy

Fr Laurence Ginaty sm

Compassion for the Rejected

To mark the Year of Mercy, this article is one of a series of reflections on the lives of Marists who have worked in New Zealand, and in whose lives mercy has shone. It was first published in the SMNZ newsletter.

The exploitation of young women and girls in industrial bondage and sex slavery is as old as history itself. So I felt proud to read of the work of our Marist team in Ranong, treating those with AIDS and providing many with an education able to free them from the cycle of poverty, degradation and early death. It is strange to imagine this in a New Zealand scenario, especially amidst the prim society of the descendants of the first four ships in Christchurch. Yet that was the setting of the work of Laurence Ginaty at Mount Magdala in Halswell in the south-west of Christchurch.

It was the experience of encountering poverty and prostitution as a prison chaplain that fired Ginaty. He had a vision of a refuge, a home that would make possible a new life for such young women and children. It took years of hard work before this vision began to take shape with the help of two sisters of the Good Shepherd on the small farm at Halswell.

By the time of his death in 1911, Mt Magdala had become a local legend. Through the work of a commercial laundry and other small businesses on the property, it had become nearly self-sufficient. Its family had grown to 25 sisters, 159 young women, 62 orphans and eight workmen. The women usually stayed two years, picking up practical skills and learning, ready to live a new life with their own bank account, sometimes in a new place and under a new name.

Pre-Mount Magdala

Born near Dundalk in County Louth, Ginaty was fortunate to come from a well-off farming family able to give him a good education. A committed student, as a youth he felt the strong desire to become a priest and missionary. After making contact with the newly arrived Marist community at St Mary’s College in Dundalk, he intensified his literary and theological studies and made his first profession on the feast of the Immaculate Conception 1865. He was then aged thirty. After ordination, he taught for ten years mainly at CUS in Dublin and during this time got to know Francis Redwood – a relationship that would shape his future. Soon after his appointment as bishop of Wellington, Redwood had to make a tricky appointment of a parish priest in Christchurch, so he called on Ginaty.

At this time, 1877, Christchurch was still one large sprawling parish split by different factional interests: older established English families up against new Irish and Polish immigrants; those delighted to welcome an Irish pastor as against those fiercely loyal to the previous saintly but sickly John Chareyre. By his zeal and dynamic personality Ginaty managed to unify these elements within his first few years there.

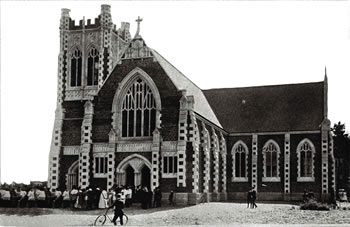

What impresses an onlooker about this man is his seemingly boundless energy. Very quickly he enlarged the church of the Blessed Sacrament, adding a most impressive organ and a set of bells. He opened an academy for boys. At one stage he had eight different projects on the go. He started planning for a church in Papanui, and drawings were made for a possible cathedral. Trying to juggle repayments, he transferred monies from one account to another. Such alarming rumours reached Wellington that the Marist administration sent Frs John Forest and Francis Yardin to do an audit. Ginaty’s integrity was vindicated but at the price of a scorching dressing down from his bishop.

As chaplain to the city’s prisons, Ginaty reconciled an intelligent young Irish woman whom he met in Lyttelton gaol in Easter 1886. Later that year he was called to give her the last sacraments as she lay dying in a backstreet abortionist’s den. This incident led him to direct and focus the rest of his life as a priest.

Background to the establishment of Mt Magdala

Julius Vogel’s immigration policies of the 1870s had done much to build up the population of the young colony. Though the new-comers included some skilled artisans and farmers, many more were migrants from troubled parts of the Austro-Hungarian empire, from German-dominated territories, or were unskilled rural labourers from Ireland. Many of the Irish men settled in South Canterbury or Taranaki, while young Irish women worked as maids in hotels, or with wealthy families as nannies or nursemaids. During the 1880s the economy began to slump. The goldrush on the West Coast was running out of steam, and the best agricultural land had been taken up by a relatively small number of gentlemen farmers. Many poor Irish men ended up in cities like Christchurch and young women were forced into prostitution. Sectarian tensions, between followers of the Irish Fenians and members of the Orange Lodge, began to rumble and fester. Ginaty himself, on Boxing Day 1879, had to intervene to stop an incipient brawl between a group of his Irish parishioners and an Orange Order parade, processing down Manchester Street, on its way to board a train heading to a rally in Timaru.

It was against this background that Ginaty began the project which was to become Mt Magdala. He started preaching missions and travelling widely, pledging the money raised to the new project. It is in this context that his personality and spirituality shine out. Strong and outspoken, sometimes blunt and forceful, he went ahead where others would have blanched and retreated. He used the story of Maggie, with great effect, to congregations all over New Zealand and to editors and reporters, but kept his own role and personality well in the background. He had a great devotion to Mary Magdalen, and like her, felt impelled to take the story of Christ’s mercy and healing to the world regardless of what it might think of him.

When Redwood finally gave him permission in mid-1886 to make Mt Magdala his main work he had already been collecting funds determinedly. His mission had taken him to some of the most isolated North Island bush country, leading him to go under the radar south of the Waitaki river, where Marists had become persona non grata after the nomination of the English Marist, John Grimes, to Christchurch – in the face of the urgent demands of Bishop Moran of Dunedin, who had fought for the installation of an Irish secular bishop. Ginaty rarely missed the chance to publicise his mission. In 1886 he succeeded in persuading Cardinal Moran of Sydney, travelling between consecrations and openings in Dunedin and Wellington, to bless the foundation stone for Mt Magdala, this despite the fact that all that surrounded the crowd gathered for the occasion were empty, wind-blown fields. He raised over £1000 at this gathering. The next year he started building despite the fact that the Good Shepherd Sisters who had promised to come were still marooned in Melbourne, fighting the total opposition of their archbishop to their departure.

Much of his success came from the sympathy Ginaty was able to elicit from people of all levels of society and every faith. He gave excellent copy to newspaper editors and received many and generous donations from numerous non-Catholics. It was such drive and commitment that allowed him to programme the solemn opening of the completed buildings on 22 July 1888.

In 1894 Ginaty settled on the property of Mt Magdala as manager-chaplain. The project flourished, enabling him to focus more and more on his pastoral work with the young women, teaching, counselling, encouraging, building up their human and spiritual resources. Great was the sadness there in 1907 when Bishop Grimes asked him to become his Vicar General and parish priest at St Mary’s church Manchester Street. When he died there suddenly on the afternoon of Pentecost Sunday four years later there was a general outpouring of grief. The cathedral was packed with both Catholics and non-Catholics and after the funeral it was a sad procession that made its way to the little cemetery at Mt Magdala where he was laid in his grave amid the wailing and tears of those to whom he had devoted so much of his energy and love. This was a life of practical compassion, one that transformed his rich gifts of drive, energy and profound sense of mercy into an institution that provided hope for hundreds of those destined otherwise to misery and degradation.

Tagged as: Laurence Ginaty, Mt Magadala

Comments are closed.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)