Mary for Today

Mary in the Year of Faith: ‘Conceived of the Virgin Mary’

Concerning the biblical origins of this traditional belief in the Blessed Virgin, two points need to be noted:

1. Only the virginal conception of Jesus is directly mentioned in the New Testament;

2. As a result, for the New Testament, the emphasis is placed not so much on Mary nor on the virginity as such, but on Jesus and the great new event signified by the virginal conception.

Although the church has never offered a dogmatic formulation on the virgin birth, of Jesus from Mary, it does consider this belief among its dogmas. Only Matthew and Luke give us an account of the conception, birth, and, in Luke, the early life of Jesus. These narratives were the last part of the gospels to come into being, and they are not on the same historical level as the narratives that tell us of the public life, death and resurrection of Jesus. Yet two gospels present a virgin birth as a completely miraculous act of God; both versions of the infancy differ so much in detail that their discrepancies are in fact irreconcilable. But the two of them, independently, are interested in the conception of Jesus by his virgin mother as a sign of divine grace and choice. The truth they express is that Jesus’ origin was in God and that he was God’s Son and Messiah from birth.

Mary is mother of the Messiah through an extraordinary action on

the part of God.

If the genealogy of Matthew is unconventional with its mention of four women, then so is Mary’s conception of Jesus through the power of the Holy Spirit and her own ‘Yes’ to God’s plan for her life. In God’s sovereign initiative a mother is chosen for the Messiah. In the early church there was a Docetic (only seeming to be real) notion that the Messiah, coming from heaven, would appear as an adult. Matthew and Luke refute this with details about his birth and infancy. Mark insists that Jesus was the member of a human family.

Matthew’s Mary: Mary and Joseph are ‘betrothed’, a far more binding relationship than ‘engaged’. Customs in Israel regarding betrothal differed; girls were betrothed shortly after puberty, and after a year took up residence with their husbands. They live in Bethlehem (different in Luke) where the child is born. Only on their return from Egypt do they move to Nazareth. Sexual intercourse in Judea during betrothal was frowned on by stricter rabbis, but was widely accepted as it transformed the betrothal into full marriage. If Mary had lived in Judea her pregnancy would have been no cause for blame if it was known that Joseph had visited her. Only if he denounced her would she be subject to stoning for adultery. If they lived in Galilee, Nazareth (Luke’s picture) then premarital intercourse would have been against the customs. Mary would have been more liable to blame and punishment.

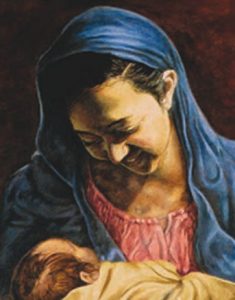

Matthew shows us that the condition of Mary was fully accepted by Joseph. He trusted the message of an angel in a dream. Through this prophetic experience he understood the uniqueness of the conception of Mary’s child as both intended by God and foretold by Isaiah (7:14), though the original reference was to the birth of a child to the new wife, the young woman, and King Ahaz. In the writings that Matthew knew (the Hebrew Scriptures and rabbinical writings) a ‘virgin birth’ referred to a conception that had taken place before there was any evidence of fertility. The virgin mother and child image was important for Matthew’s community as a reminder of a loving God, faithful to God’s promises, and bringing in a new time for the world.

In Matthew’s account, Mary is constantly associated with her child, as in the visit of the magi. Joseph acts as designated protector of both, as in the flight into Egypt, the return, and for the first time, the choice of Nazareth as place to settle. Joseph is the leading figure in Matthew; the annunciation of the angel is to Joseph, as are the dreams which shape much of the action. Joseph then abstained from having sexual relations with the child’s mother, as though she was under sacred taboo until the birth of her God-given child.

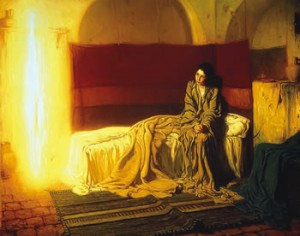

Luke’s Mary: A reminder is in order; every gospel is a post-resurrection proclamation of Christian faith. This gospel gives considerable stature to Mary; unlike in Matthew, she is the centre of action. Mary is presented as the first to hear the gospel. She does not fully understand the meaning of events, but in pondering ‘these things in her heart’, she seeks to understand their meaning. The heart of his infancy narrative is the annunciation to Mary, set between the annunciation to Zechariah and Mary’s visitation to Elizabeth. The angel’s annunciation to Mary is concerned with the greatness of Jesus.

Luke’s Mary: A reminder is in order; every gospel is a post-resurrection proclamation of Christian faith. This gospel gives considerable stature to Mary; unlike in Matthew, she is the centre of action. Mary is presented as the first to hear the gospel. She does not fully understand the meaning of events, but in pondering ‘these things in her heart’, she seeks to understand their meaning. The heart of his infancy narrative is the annunciation to Mary, set between the annunciation to Zechariah and Mary’s visitation to Elizabeth. The angel’s annunciation to Mary is concerned with the greatness of Jesus.

“How can this be since I am a virgin?” alt. “I am not knowing a man?” It is unfair to expect the scriptures to do more than they are meant to do. Knowledge of preceding annunciation and birth stories spread throughout the Bible gives an indication of what is happening here. Too often this question is taken as a biographical statement of Mary’s puzzlement. Wishing to avoid the banal explanation that she did not know how children were conceived, fourth century church Fathers argued that Mary had already taken a vow of virginity. This came in line with a growing post New Testament tradition that Mary remained a virgin for the rest of her life. Such an intention at the time of her betrothal would have invalidated any marriage to Joseph and be quite contrary to Judaism.

In accordance with the Bible’s own annunciation patterns what we are dealing with here in 1:34 is an objection that is a standard feature of the literary form. Zechariah did the same: “How can this be since I am an old man and my wife is advanced in years?” In Mary’s case, it offers the angel a chance to explain that the conception will be virginal and to give the sign of Elizabeth’s pregnancy. The angel’s words to Mary, especially the language about ‘Son of God’ and ‘Messiah’ dramatise vividly what the church had to say about Jesus after his resurrection and during his ministry after his baptism. This Christology has been carried back to Jesus at the very moment of his conception in his mother’s womb.

The incarnation points to the mysterious origins of Jesus in God. What is special about him cannot be explained by human parentage alone but is due to God’s creative initiative. Mary’s virginity speaks of her holiness, of her being receptive to the Holy Spirit. It is this focus that is the important stress in the account rather than the absence of sexual relations. Jesus is ‘born according to the Spirit’ (Gal 4:29). This is one area in which a distinction needs to be made between what belongs to the essential content of faith, and what belongs to a secondary level.

References: Brown, R. E. et al. Mary in the New Testament.

Coyle, Kathleen, Mary in the Christian Tradition.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)