Mary for Today: Part 9 – Gospel of John

Mary in the Gospel of John

John gives two key places to the Mother of Jesus in his gospel: Cana where Jesus officially starts his public life with his first sign, the best wine; and the Cross, the flow of blood and water, the final sign, where Jesus ends his public life.

Mary at Cana (John 2:1-11). Amid the feasting, dancing, and singing of the wedding, the wine gives out. The mother of Jesus notices, and brings this to Jesus’ attention but he declines to get involved for ‘my hour has not yet come.’ Disregarding his hesitation, she bids the servants to follow his word, which they do, filling to the brim six stone water jars with a capacity of twenty plus gallons. Biblical scholarship tells us that the story of Cana has all the earmarks of a popular story or folktale, originally circulating to express people’s interest in the early, hidden life of Jesus, similar to the finding of the twelve-year old boy in the temple. Such stories exist as one type of literature that carries God’s message of salvation. “The evangelist is not responsible for the origin or historicity of a story; he is responsible for the message it serves to vocalise.” (R. E. Brown).

Quite clearly the main purpose of the Cana narrative is Christological, to reveal the person of Jesus gifted with the glory of the Messiah. In the coming days ‘the mountains shall drip sweet wine, and all the hills shall flow with it’ (Amos 9:13). The 120 to 180 gallons of wine signify the abundant salvation for which light, water, and food are other Johannine symbols. With such abundant symbolism it is not surprising that the mother of Jesus is never given her personal name but functions strongly at the symbolic level as image of the true believer because of her faith in Jesus.

Mary’s presence in this scene ties Cana to the cross, the other Johannine scene in which she appears and where Jesus’ hour has now come. While highly symbolic, this Cana story is grounded in the historical reality of its time. A festive wedding supper with friends and relatives lasted through the night into the next day. The stone water jars add another authentic note, stone jars being preferable to clay pots.

That ‘they have no wine’ is more than an embarrassment to the providers of the feast and the couple. It is a painful reminder of the precarious economic situation in which the wedding guests all lived. Mary named the need and took initiative to seek a solution. Because she persisted, a bountiful abundance soon flowed among the guests. Far from silent, she speaks; far from passive, she acts; far from being subservient to the wishes of her son, she goes counter to his wishes, finally bringing him along with her; far from yielding to a grievous situation, she takes charge of it, organising matters to bring about benefit to those in need.

With the words, “Do whatever he tells you”, the mother of Jesus alerts the servants to listen to his word and follow his way. In John’s Gospel women play surprisingly significant roles, both in the number of incidents recounted and their theological consequence: the Samaritan woman, Martha of Bethany, Mary of Bethany, Mary Magdalene. The mother of Jesus gives her instruction to the servants at the wedding feast, charging them to turn believingly to Jesus. They do so on the strength of her testimony.

Meaning? All humanity and Judaism had to offer was six water jars for ritual cleansing, insufficient for a wedding feast. It is only through Jesus’ death and resurrection ‘on the third day’, that the mundane and ordinary is replaced, transformed into the glorious new wine of God’s promised fulfilment. The meaning of the whole of this gospel is ‘sign-alled’, prefigured in this first sign.

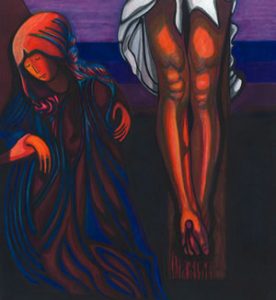

Mary at the Cross (19:25-27). Death as an act of violence causes unnameable grief in the hearts of those who love and lose another. John’s gospel gives us in brief shorthand the scene: John 19:25-27 “Meanwhile, standing near the cross of Jesus were his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, ‘Woman, here is your son.’ Then he said to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home. “

Many works of art conjure up all the anguish and desolation a woman could experience who had given birth to a child, loved that child, raised and taught him, even protected the child only to have him executed in the worst imaginable way by the power of the state. The gospel never describes Mary as holding the body of her dead son when he is taken down from the cross, yet the artistic image of the pieta captures the inexpressible sadness at the heart of this event.

The presence of women at the cross is attested in all four gospels. A group of them kept vigil, standing firm in the face of fear, grief, and the scattering of the male disciples. There is no mention in the Synoptic tradition of the mother among the women at the cross. Luke places her in Jerusalem with the community at Pentecost. The gospels stress that all the male disciples fled. This unnamed beloved disciple, probably not one of the twelve, plays a role that is utterly peculiar in John’s gospel. He is the witness who guarantees the validity of the Johannine community’s understanding of Jesus.

The two great unnamed figures appear together, the mother of Jesus and the beloved disciple. They are both historical persons but are not named because they function as symbols of discipleship. Standing by the cross they are turned towards each other by Jesus’ words and given into each other’s care. Henceforth they represent the community of true believers that it is Jesus’ mission to establish. They mark the birth of a new family of faith, born in blood and water, and founded on the following of Jesus and his gracious God. Jesus reinterprets family in terms of discipleship. There is symmetry between the woman and the man; mother and son; both are equal partners in the family of disciples, functioning as representatives of a larger group, the church.

Uncovering the symbolism of the mother/beloved disciple scene links Jesus’ death, the gift of the Spirit, and the foundation of the Christian community. Mary as a precious symbolic figure has the unfortunate effect of deleting her human reality as an historical woman with a crucified son, something that has continued for much of church history. Even if she did not stand at the foot of the cross in three gospels, even if she was still in Nazareth - the more likely event, news would soon have reached her. Her grief would be no less, and she joins the many women who experience such loss at the hands of the powers that rule to serve their own interests, among the women who cry out: “No more killing of other people’s children!”

Closing Reflection: Pope John Paul II in speaking to the four leaders of the Marist orders told them, “It is up to you to show in original ways the presence of Mary in the life of the Church and in the life of people.” Both Cana and Calvary in John demand our attention. In Cana we are given Mary’s last recorded words, “Do whatever he tells you.” We find that in the word of the Scriptures. Calvary and the flow of blood and water remind us of Baptism and Eucharist. Scripture and Sacrament are the heart of our existence as Church, the source of renewal and new life, of unity in our divisions, of renewal in weariness, of new life in stagnation. Mary, our caring mother, points this out to us.

References: R. E. Brown, Mary, the First Disciple.

E. A. Johnson, Truly Our Sister.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)