The Hours of Catherine of Cleves

A Medieval Lesson in Prayer

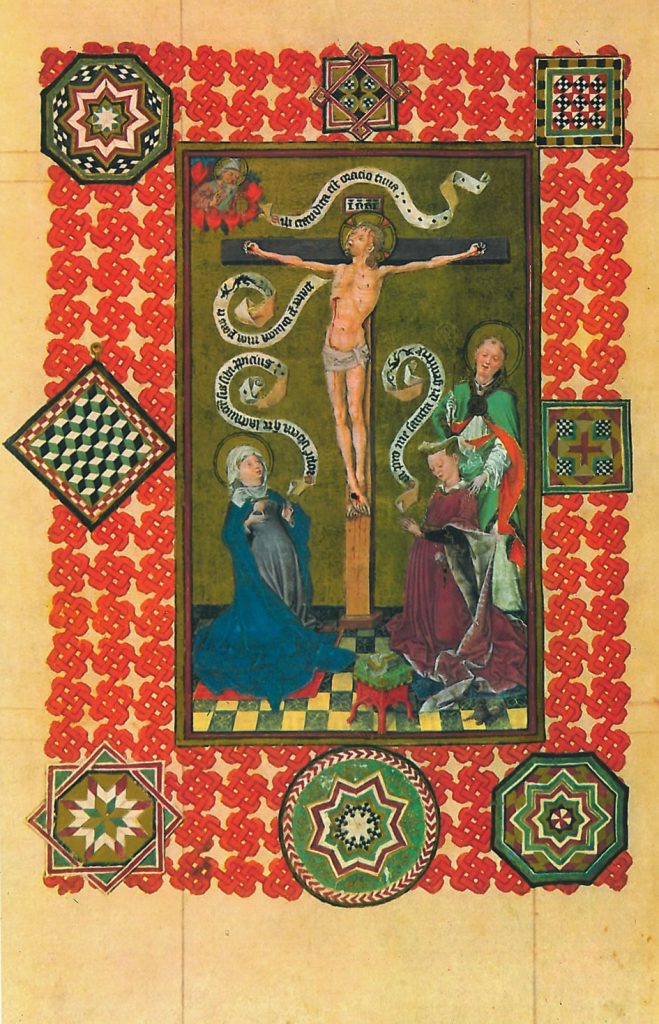

I have recently been lecturing about Medieval Art which has led me to look closely at some of the beautiful images from our past. Fr Brian, the Editor of the Marist Messenger, attempting to elicit a column from me for this issue, told me of some of the other articles that are appearing. The Cross seemed to feature in many ways. This brought to my mind the image on the facing page. It is a full-page miniature from an illuminated manuscript called the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, painted by an anonymous artist about the year 1440. A book of hours is the prayer-book of a lay person, in this case it is Catherine’s. She was Duchess of Guelders in the Netherlands and she used this book in her daily prayer and while attending mass.

Private books of hours are semi-liturgical. They could be used for personal prayer but were usually used in common and were patterned on the Liturgy of the Hours prayed by religious. Catherine was wealthy and noble (she was the great granddaughter of Jean le Bon, King of France) and her book is one of the great masterpieces of medieval art. It is art intended for a well-educated, pious lady.

Bordering the scene is an elaborate pattern of orange interlace knots on which are hung panels of intarsia work. The knot-work could well be a piece made by Catherine which the artist has skilfully depicted as if it lay on the page. Catherine herself is pictured at the right of the crucifixion scene, with her rosary beads over her arm, and her book of hours open on the stool in front of her.

The anonymous artist has imagined her at prayer and in the very direct medieval style is showing just what effect prayer can have. Behind Catherine is a saintly bishop, possibly Nicholas who was the patron of her chapel. Anyone coming to present themselves in a medieval court would come recommended and ideally accompanied by their patron. Here Catherine is coming before Christ accompanied by a patron saint. The banderol in front of Catherine has the words of her prayer, directed not to Jesus but to his mother. “Pray for me, Holy Mother of God.” In response, Mary presents her claim to be heard by Jesus in the most direct and dramatic way. She shows her breast and says “Be gracious to her for my sake, and the breasts that suckled you.” If Mary’s argument is backed up by her mother’s milk, that of Jesus is supported by his life’s blood. Jesus says to God the Father “In the name of my wounds, spare her.” In the midst of his angels in heaven the Father responds “Your prayer has been heard with favour.”

The earthiness of this medieval image can be shocking to our modern sensibilities but I consider it a gorgeous portrayal of how prayer and liturgy work. For prayer to have power it has to work through Jesus Christ, the God-man – his is the only name by which we can be saved, which is another way of saying that only he connects heaven and earth.

All liturgy is directed through the paschal mystery, the saving death and resurrection of Jesus. Baptism takes us into the death of Christ and we rise with him to new life, the Christian life. When we gather to pray as Christians we come into the presence of Christ. Moreover, we come as a group – prayer and liturgy are not solitary activities, we pray with others and that includes those who have gone before us, most especially the great pray-ers of the past, the saints. Those who pray with us help us and make our prayer stronger and more honest. Liturgy and prayer work on our bodies as well as on our minds. Posture, touch, reverent action, holy things and holy places all affect and enhance prayer. We bring the work of our hands and our whole selves to prayer and we come away changed.

Catherine’s book reminds us just how much our patrons and the Mother of God can help us in our prayer.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)