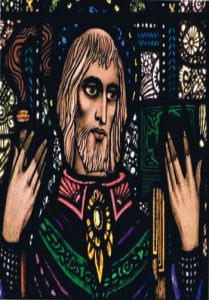

1400th Anniversary Of The Death Of Saint Columban

The greatest of the Irish missionaries who ministered on the European continent in late antiquity, Saint Columban was born in the Kingdom of Meath in 543, the year Saint Benedict died at Monte Cassino. Columban’s family was wealthy and he received a good education in the areas of grammar, rhetoric, geometry, and the Holy Scriptures. As a young man Columban was tormented by temptations of the flesh, so he sought the advice of a hermit and saw in her answer a call to leave the world. Despite the opposition of his mother (who literally threw herself across the doorway to try to block him), Columban left home to become a monk.

He first became a monk with Saint Sinell, under whose instruction he composed a commentary on the Psalms. Columban later moved to Bangor Abbey on the coast of Down, where Saint Comgall was abbot. In doing so, Columban was joining the most austere branch of Celtic monastic training. Columban made his monastic profession in Bangor and was ordained a priest. Desiring greater self-sacrifice, Columban asked his abbot if he could go into voluntary exile, leaving his native Ireland to start a monastery on the Continent. There were two degrees of peregrinatio pro Christo, “exile for Christ,” a lesser one practiced in the form of a self-chosen exile within Ireland and a stronger one by leaving Ireland. Columban chose the stronger form.

For quite some time, Abbot Comgall refused to grant permission for Columban to leave Bangor. In his decades at Bangor, Columban had proven himself to be a devout monk and an able teacher. Comgall was reluctant to lose what we now might call his “right hand man.” Eventually Comgall agreed and Columban, with twelve companions, set out on his wanderings for Christ, probably in 590. And so, nearing the age of fifty, Columban left Bangor monastery to begin missionary work in Europe, where, after the collapse of the Roman Empire, entire regions had lapsed into paganism. Arriving in Gaul (modern-day France), the monks won wide respect for their discipline, their preaching, and their commitment to the religious life in a time characterized by clerical laxity and civil strife. Beginning in Brittany, Columban and his companions established monasteries at Annegray and Luxeuil. These became centers of religion and culture, brought by the monks from their native Ireland.

The French people were inspired by the lives of the monks and came to them for prayer and healing. So many young men were inspired by their religious zeal that soon dozens of monasteries were formed, looking to Columban as their spiritual father. The Irish monks with their new, forceful kind of Christianity, stressing self-discipline and purity of life, presented a striking contrast to the complacent churchmen already living among the Franks. Columban’s strict adherence to monastic discipline made secular clergy who had committed simony and adultery feel uncomfortable.

Columban’s stress on moral teachings led to conflict with the local bishops and the Frankish court. In Gaul at that time a sinner had to do public penance, in sackcloth and ashes, for many years before the bishop restored him to communion. Pardon was granted only once in a lifetime. The penances were so severe that many postponed confession, or even baptism, until their deathbed. Columban brought to mainland Europe, the Irish system in which a sinner could be forgiven more than once, even by a priest, and penances were carried out in private. (Sound familiar? We owe to the Irish monks the system of private penance which the Church has used for many centuries.) But don’t think the Irish confessors would only assign easy penances. There were also tougher ones. For example, if a person decided to kill, or commit fornication, or steal, but didn’t do the act, the penance might still be living for half a year on bread and water.

Many Frankish bishops resented a foreign missionary with so much influence, as well as the Celtic practices he brought, especially those related to private penance and the date of Easter, and perhaps most of all his independence from them. During the first half of the sixth century, the councils of Gaul had given to bishops absolute authority over religious communities. Columban’s independence of action ignored the bishops’ prerogative. In 602 he was summoned to appear before the bishops for judgment; instead of appearing, he sent a letter advising them to concern themselves with more important things than which rite he used to celebrate Easter.

Columban also angered members of the French royal family. When King Theuderic II of Burgundy began living with a mistress, the saint objected, earning the displeasure of the king’s grandmother, Brunhilda of Austrasia. She feared a royal marriage would threaten her own power. Brunhilda became Columban’s bitterest foe(.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbanus - cite_note-cusack-13) Angered by the saint’s moral stand, Brunhilda stirred up the bishops and nobles to find fault with his monastic rules. Theuderich demanded access to all areas of Luxeuil monastery, something Columban refused outright. King Theuderich decreed that monks who cut themselves off from the world must leave Burgundy and return to their countries of origin. Columban was taken prisoner to Besançon. Columban briefly escaped his captors and returned to his monastery at Luxeuil. When the king and his grandmother found out, they sent soldiers to drive him back to Ireland by force.

Columban was taken down the Loire river to the coast. But soon after his ship set sail, a severe storm drove the vessel back ashore. Convinced that his holy passenger caused the tempest, the captain refused further attempts to transport the monk. Fortunately other kings did welcome Columban into their territories. Columban arrived in Milan in 612 and (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbanus - cite_note-16immediately) began refuting the teachings of Arianism, which denied the divinity of Christ, and which had enjoyed a degree of acceptance in Italy around that time. Queen Theodelinda, a devout woman, played an important role in restoring Nicene Christianity to primacy over Arianism, and was largely responsible for her husband the king’s conversion. At Bobbio in northern Italy, Columban started what was to be his most important monastery. He and his monks worked for the conversion of the Arian Lombards and the restoration of their unity with Rome.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbanus - cite_note-edmonds-1)

When he knew his time was near, Columban went into a cave alone and stayed there until he died on November 23, 615. After his death, both the Irish and the Italians were very devoted to this wonderful missionary. In a sermon ,Columban, the pilgrim for Christ, once said, “Since we are travellers and pilgrims in the world, let us ever ponder on the end of the road, that is of our life, for the end of our roadway is our home.”

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)